Dear Friends,

Maybe this is a topic that would have been better for application season itself this past fall—but it’s never too late for an intervention before someone makes a terrible mistake. Someone recently asked me if I could write a newsletter update regarding my thoughts on MFA programs. I said that I generally try to write my newsletters in a way that prioritizes honesty, helpfulness, and a compassionate delivery of information. I said I could certainly not guarantee the latter—or—at least that being brutally honest with regards to MFA programs would be its own type of kindness. I was encouraged to proceed.

Be careful what you wish for.

To be honest, I don’t know what the conversations about MFAs center on now. Back when I was first looking at programs in the late aughts, most of the frenzy was focused either on “rankings” or this feverish accusation that MFA programs were these insidious machines you entered only for faculty to brainwash you and spit you out with a generic “MFA writing style” devoid of all personality.

Fortunately, it seems that most of us have come around to the conclusion that letting one or two people rank all the MFA programs in the country is, for a lack of a better word, problematic. Additionally, most people who go into an MFA program have enough knowledge of their own interests to grow inside them. No one is brainwashing anyone. In any case, if you’re the type of person who has no conception of your own work and you would let a professor completely imprint their own style and aesthetics on you, then it would probably be better to emulate someone like David Baldacci or Sarah J. Maass rather than some obscure lit fic writer in the ivory tower. At least those people make millions.

Okay, maybe I’m about to get a little dry or a little wicked or a little flippant. My thought on the MFA has always been it is this thing you can or cannot do and it does not matter. My thoughts were and continue to be it is an opportunity for you to pause various aspects of your life and shift focus to your creative writing. I don’t even have strong feelings about my own MFA. I liked it more than I disliked it. I made a few incredible friends, worked with some faculty I admire who encouraged me and mentored me, and was fortunate enough to be in a space where my risks were encouraged. The work I was doing 10 years ago was certainly more experimental in certain regards than what I’m doing now, and I know there are many programs where my experiments would have been trashed or discouraged. Although there are some downsides to being permitted to mess around with abandon, it was also the right space for me at the right time in my life.

At the end of the day I cannot tell you what will work for you or not work for you. However, perhaps I can ad lib some thoughts with my guiding newsletter principle that I hope I can throw at least one thing your way that you can take away and learn from. I don’t even know what my 40 points will be, but it sounded like a good number when I wrote the post title. Okay. Let’s do it. Let’s go to clown town.

Without further ado…

40 Thoughts on the Creative Writing MFA

Holding an MFA degree is relieving in the way that passing a kidney stone is relieving.

If you have never worked a retail or food industry job, you should go work some terrible job facing the public between your undergraduate degree and graduate degree. You need to have a shopper destroy a pile of t-shirts you just immaculately folded. You need to have a diner shout at you because you included a lemon on the saucer and they asked you to bring the lemon inside the water. You need to have your graphic design client tell you that you need to ‘make it pop more’ without any additional concrete feedback. You need to watch that man who comes into your coffee shop every day to spend $9 on a latte tip you a nickel. Or, if you’re really a masochist, try working for a non-profit for a couple of years. It could make the best atheist believe in hell. I know, I know, there are plenty of people who by the time the turn eighteen have enough to write about for the rest of their lives. I’m not necessarily saying this to suggest that all people who have never existed outside of school have nothing to write about, only that people who go straight from kindergarten to grad school are about as socially appealing to me as Gollum climbing around on all fours whispering to himself about what has it gots in its nasty pocketses.

I lived in NYC for most of my twenties and the better part of a decade before I went back to school. Awhile ago, there was this “MFA vs. NYC” debate. It is a tedious dichotomy—and a false one. However, it is possible to be part of communities that have nothing to do with academia. I have found these communities the most rewarding. It also used to feel more punk to say I didn’t have an MFA. Alas, I have been compromised. I will say that my life in literary and publishing communities in New York led me to more opportunities than my MFA did. However, this is just one person’s experience. Both the city and my degree offered me pathways. In my experience, the answer is both. That being said, I’m pretty biased as a New York apologist. I’m glad I spent most my twenties at raves in warehouses under the BQE rather than learning the difference between fabula and syuzhet in a cornfield. For me, on the cusp of turning thirty was the perfect time to begin settling down and thinking seriously about writing and what I wanted out of my “one wild and precious life” (thank you, Mary).

You should create a hierarchy of your needs before you begin applying to any programs. If funding is the most important aspect, you should only apply to programs that provide fully-funded packages. If you only want to be in or near large cities, don’t apply to schools in rural areas. If you tend to feel claustrophobic in small groups, don’t apply to a program that admits one person in each genre per year. You’re going to be stuck in that program or place for a few years, so be honest with yourself about what your needs are—otherwise you’re setting your future self up for a bad time.

You should also budget before application season arrives. Graduate school apps are wildly expensive. The GRE is a racket, although it seems many programs are slowly getting rid of that requirement. Your undergraduate college(s) will charge you for each official transcript. Save up now, honey. Although, if you’re working class, don’t be afraid to ask what types of application waivers are available.

There’s a lot of big talk out there about applying and getting into MFA programs… but the unfortunate reality is for a lot of people though: you’re going to have to settle for where you actually get in and who offers you the most money.

Don’t go anywhere for faculty. Mainly for this reason: just because someone is known for being at a certain location (even tenured professors), doesn’t mean they’re not planning on quitting or retiring or moving. In addition, just because you love someone’s writing doesn’t mean they’re an effective teacher. You know what they say about meeting your heroes. The inverse: just because you’ve never heard of someone doesn’t mean they’re not an incredible teacher or mentor.

Moderate your dreams about what the MFA will lead you to. You should understand that even people with well-received debut novels on Big Five imprints or even multiple books don’t necessarily live as full-time writers. Writing doesn’t guarantee a salary, doesn’t guarantee insurance, doesn’t guarantee prestige…. Even many successful people you follow online get by from speaking gigs at universities, temporary faculty positions at writing conferences, and their regular ole day jobs. Advances and royalties don’t mean much for a lot of writers. Your interest in this should be based out of aspirations beyond fantasies of wealth, fame, and job security. There are a lot of middle-career writers you’ve never heard of, and even to get to that point is an honor.

The literary world operates on prestige, but it also tries to pretend it is beyond star-fucking. It’s not. Having a largely successful debut novel the same year you’re going on the academic job market will greatly benefit you. Getting an MFA from Iowa or an Ivy League school (Columbia, Cornell, Brown) will most likely benefit your career goals over some no-name school in a fly-over state. This is not to suggest that you will be entitled to or even guaranteed any opportunities, only that the type of people who are impressed by things like Ivy League diplomas will be impressed by your Ivy League diploma. And boy, there sure seems to be a lot of these people in positions where they can hold the gate shut.

That being said, ‘rankings’ are bullshit and biased. Go because a program fits your needs, not because you saw it in a 2013 issue of Poets & Writers or an Excel spreadsheet. Additionally, ranking full-time programs above part-time or low residency programs is also bullshit. Not everyone can drop their life and move across the country to pursue a full-time degree in writing—especially if you’re older and/or have a family and/or have an established career.

Most MFA programs are centered on this idea of the program as this type of protected time/space where you get to focus solely on developing your writing as well as develop yourself as an author. What this means is that the program is the literary equivalent to a studio art program. If you are being trained to be familiar with any type of space, it is a type of space that is more closely tied to literary fiction, academic poetry, and the type of writing that, fittingly, finds its home in MFA-staffed literary journals.

Once a commercially, traditionally published friend told me she was gobsmacked that MFA programs did not teach much about the publishing process. I iterated my previous point (MFA programs being centered on a type of ‘art-making’). That being said, I did agree with her completely. The whole ‘if we talk about publishing we are violating the sacredness of this protected writing time’ is a common stance for many MFA faculty, although one I will say it is dubious. It operates on this erroneous assumption that either A) everyone is engaging in a type of art-making that does not aspire to be the type of writing that will enter the traditional publishing process or B) that publishing is this DIY process that everyone most learn for themselves.

I would argue that it is the responsibility of every MFA program to have an optional course or elective on publishing. For many people, they do need to know the difference between an agent and an editor; how to write a query letter; that agents should not charge up-front fees and should only take a standard 15% percentage out if a book sells; and so on. If you hold this knowledge and you do not share it, not only are you doing your students dirty, but you’re engaging in a type of unnecessary hazing. What this also means is that if you are a prospective student who is interested in publishing, you should ask the program you’re applying to how they prepare students for publishing.

If you work in genre: fantasy, science fiction, horror, young adult, thrillers, romance, mysteries…, unless you are interested in trying to place your work in the hands of literary readers, it might be best to locate workshops or conferences or online spaces that cater to your specific genre. There are a lot of people who still look down on genre writers. These people are rubes. Having attended Clarion for a summer is generally more valuable to most science fiction and fantasy writers’ careers compared to spending three or four years at an MFA program. It’s never too early to think a little harder about the work you do and who it is for. Place yourself in the space you want to be in. If you place yourself in a space with people who are not readers for your genre (or worse, refuse to engage with it), you’re setting yourself up for failure.

“Protected time and space” is also an illusion. You might have to deal with unpleasant or envious peers and faculty; tedious graduate assistant or instructor roles; the mental health toll of moving to a college town in the middle of nowhere, etc. You should also be aware that when you teach for three or four years that your career temporarily shifts into the education field, whether you like that or not. You should consider your interest in teaching ahead of time and consider how potentially teaching for half a decade will impact your overall career goals. Shifting your life focus to creative writing is a trade-off, and it’s important to consider what you will be giving up or moving away from before you commit.

A lot of MFA programs prey on young people because they’re easier to convince that teaching 120 students per year for $12,000 is a great arrangement.

I was making $12,000 per year and my landlord who owned two houses (three if you include the carriage house behind the one I rented that he sometimes stayed at) asked me if I could give him our WiFi password.

Don’t give someone who owns three houses your WiFi password if you are making $12,000 per year.

If you do get accepted into multiple MFA programs, you should play hardball and pit their funding offers against each other to try to come out with a better funding package. Unless you’re independently wealthy, you’re probably going to come out of this thing in the red, so it would serve you best to start advocating for yourself now as the first step and trying to be less financially fucked by going for a graduate degree in poetry, of all things. Also, don’t forget that most universities have this agreement where you have until April 15th to make a decision. Don’t let them pressure you to commit before that date. Don’t say yes until you hear back from every program you’ve applied to. Also, a lot can move around in that week following the 15th as people commit. You may come off some waitlists, so be aware of that.

If you get accepted into an MFA program, ask if they have any one-time relocation funds or any way to compensate you for the move—especially if you’re moving across the country. Moving is expensive and stressful and it shouldn’t come out of your own pocket if you’re moving somewhere for work (teaching and writing is work!). IRS Form 3903 got screwed up, but maybe after 2025 you’ll be able to deduct your moving expenses. You’re probably not supposed to do it for school, so here is where I say I am not a lawyer or an accountant and I am not giving you legal/tax advice.

When you arrive to your program: Don’t be desperate. Don’t name-drop. Don’t fawn. Don’t do something because someone told you it’s the only way you’ll make it as a writer. Be your own person. You don’t have to go to AWP, don’t have to go to Breadloaf, don’t have to read every debut book as it comes out. Additionally, never go in the red for any opportunity. If you cannot afford it, do not do it. Especially not on an MFA stipend. However, do ask around and see what types of internal funding, internal fellowships, conference funding, research funding, and/or travel funding exist inside your school.

Let’s talk about life in a writing program. Some people seemed to never work on their writing, and they were passive aggressive toward people who did their writing. Some people complained about not doing their writing, as if they didn’t purposefully apply and get admitted and move to a new city for their MFA program. People were passive aggressive when I said I wanted to stay home working on my writing instead of doing some social activity I did not want to do. Some people just seemed to hate being in an MFA program in general and bonded with other people over hating the MFA program and would have social gatherings where they talked about how much they hated the MFA program—as if they were trapped inside Emma Donoghue’s Room and not voluntarily part of a graduate program that they could drop out of whenever. You should probably consider whether you’re going to become one of these fuck-offs before committing to an MFA program.

Do what you want to do when you get there. No one is entitled to your time. No one in entitled to a friend group, a network, or a community just because they attend a university program. You don’t have to participate in college town culture just because people tell you there’s a culture you must participate in. You don’t have to volunteer for free labor just because your professors say service roles are within the culture of the program. As Rihanna once said: Bitch better have my money.

Be wary of alums who settle in your program’s town after they graduate if said town has a population of less than 400,000 people (New Orleans is the exception).

Try to be the best person you can be in workshops. When someone gives you feedback, try to think about who your ideal reader is and if this person is connected to that. Be open-minded. Don’t prostrate before people who aren’t your readers. At the same time, don’t assume that someone who writes incredibly differently from you does not have valuable feedback. You never know who your sharpest reader will be. Learn to filter out advice that is not helpful.

Similarly, don’t always assume that you’re someone else’s reader. Take a second to give the writer the benefit of the doubt before you assume they don’t know what they’re doing. Your experience is not their experience, and you should not assume it is. Additionally, don’t tell a person how you would have written their story or poem or essay. At the end of the day, it’s their work, and after the MFA is over they will be alone with it. Trust they are developing their voice and audience and body of work to fit their own vision.

Know when your professor is not your reader or does not have your best interest in mind.

Know that although recommendation letters have come under much criticism, they are a standard part of many professional, creative, and academic opportunities. Try to be magnanimous, professional, and treat people with kindness. They may have to testify for your character in the future.

There are moments when someone will say something that makes you feel like you’re standing naked surrounded by mirrors with a stadium light aimed down at you. Relish those moments. They are rare. Most workshops are pedestrian. When you receive a comment that makes you see an absolute truth about yourself or your writing, hold onto that.

It’s your time: advocate for yourself what you want out of each workshop. Research alternative workshopping options. Attach a list of specific questions on the last page of your writing packet if you’d like. Tell you professor you don’t want to be quiet during your own workshop if you find the ‘gag rule’ harmful to your creative process. You’re in graduate school, not kindergarten. You should be able to talk if you’d like.

However, no one likes the person who stops their workshop every thirty seconds to defend all their creative decisions. This isn’t Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney. You’re not on trial. Don’t be this person. Sign up for a workshop because you want test readers who will give you feedback on your writing. Don’t sign up because you want or expect praise. The workshop is a temporal laboratory. It does not (and should not) last forever. Baby bird is gonna have to leave the nest one day, so consider what you want out of this while you’re chewing on regurgitated worms.

Be present in workshop. When other people are talking: listen. Even if the conversation has nothing to do with you or your work. There is always learning within other people’s successes and failures. Don’t talk because you have something clever to say or talk because you want to be heard. Talk with the genuine love of trying to help another writer find a new path through their own writing. Additionally, don’t talk to reiterate something you already wrote in a workshop letter; don’t write something in a workshop letter that you said in class.

If you’re a white writer, don’t tell a person of color in workshop that you don’t connect to their characters because of the characters' race. Yes, this is racist, yes, everyone will remember it, yes, we still talk about your messy-ass behavior ten years later.

Take classes outside of workshops. Take classes outside of workshops seriously. You never know when you’ll need to pull out that term paper from that literature class as proof that you are academically capable beyond writing sonnets and flash fiction. Also, take classes outside of your department. Usually you will be required to have someone outside your department on your thesis committee, and it’s generally helpful to ask someone you already know and get along with.

Do what you can to stay out of other people’s personal lives. Protect your own personal life too. Try not to criticize other people. Stick to criticizing their work (when they’re present in the room!). Be protective of who you let into your inner circle. Don’t overshare. These are especially important in small literary or academic communities where people’s entire lives are centered around the university you attend and the department you are part of. Some of the most unhinged people you will ever meet find themselves at home in academia, and you must approach them like one approaches a vampire: do not tell them they can come into your home. Lastly, gossip is delicious in the way that eating nothing but rock candy and gummy bears is delicious. It’s enjoyable in the moment, but you’re probably going to pay for it later.

That being said, everyone experiences imposter syndrome, envy, frustration, and other negative feelings. These feelings are normal. You are not a terrible person for feeling grumpy or catty or exhausted. You are a human. We all feel shitty and need to rant or rave or talk through our problems some time. Find someone or somewhere to talk about these things that is neither a social media account or someone who is directly connected to your university. However, practice self-awareness on how much you’re dumping on other people in your lives.

You’re not an “MFA Candidate.” Stop saying that and putting it in your Twitter bios. You are an “MFA Student.” “Candidacy” is a term for doctorate degrees and generally refers to completing and passing comprehensive exams. And if your MFA program requires comps, you probably should have just gotten a PhD instead.

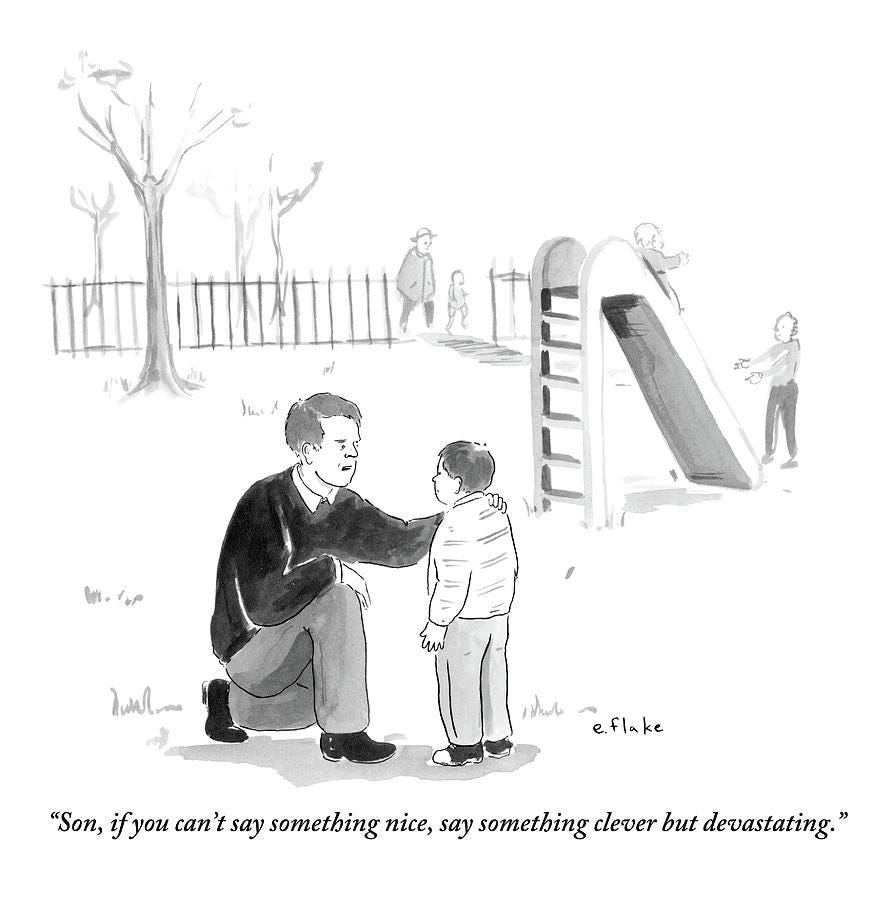

There will be non-creative people who are going to ask you, “So what are you going to do with that?” when you tell then you’re in a graduate program for creative writing. Spend some time beforehand coming up with a ‘clever but devastating’ rebuttal. These people who think the sole value of an education is to gain some trade skill that will help a person excel at capitalism deserve to be put in their place.

The summer before your final (thesis) year, start to work on an exit strategy. Revise your resume. Build a CV. Learn the difference between a resume and CV. Learn about the academic job market if you are to go on it. Explore non-academic career options. Understand the stakes of adjuncting and how full-time faculty exploit adjunct instructors. If you’re returning to the career you had before your MFA, try to figure out how it changed while you were away. Otherwise there will be a point where you have graduated and you are jobless and stuck in the place you received your degree and your stipend has stopped and rent is due.

Despite all of this, I still believe there is value in getting an MFA. I had time to dream and focus on myself. I permitted myself to slow down. I entered a life where I wasn’t just putting in 40 to 50 hours during the work week and living for the brief repose of the weekend. For a moment, I stepped outside of the rat race and got to focus on myself as a creative writer. I wrote 2.5 books during my MFA. Two of these manuscripts were under contract with university presses within six months of my graduation. My largest goal going in was completing a couple of manuscripts. I got out of my program what I wanted to get out of it. It was the right time for me. If I had gone straight to an MFA program when I was 22, I’m not sure I could have said the same. I had a lot of growing up to do after my undergraduate studies, and it’s that growing up that gave me enough experience and perception to return to grad school with confidence about who I was and what I wanted. The MFA isn’t this magical portal that will make you feel authentic, talented, or successful, but in a world that seems to devalue the humanities and arts more and more… it will give you the opportunity to exist inside a creative realm we all deserve to slip into at least once in our lives.

Yours,

JD