Fandom > Prestige

a mental shift toward embracing fan culture

Dear Friends,

In the past month I went on my first Writing Excuses Retreat (WXR), which I was fortunate to attend as part of their scholarship program. If you’re not familiar, Writing Excuses is a podcast (primarily hosted by writers who create sci-fi, fantasy, comics, game writing…) that offers free advice on the craft and business of writing.

I remember when I started my MFA a decade ago, a peer was launching a criticism at the workshop and saying they didn’t want to talk/learn about narrative elements like character, setting, plot structure, et cetera, citing that “We all learned that stuff already in undergrad!” And I was like, “Haha, yeah, we all definitely 100% did learn all that, didn’t we?”

Internally, I was freaking out because truthfully, I had not really learned about writing formally, even having taken creative writing classes in high school and college. I started to fret if I was alone in that regard (I wasn’t). Looking back, I remember reading Xeroxed handouts of writing and workshopping on the daily, but rarely did anyone ever get in front of a whiteboard with a marker and discuss the actual elements of storytelling.

Part of me still sees myself as Jenny from the Block, but I get how presenting yourself as a punk-poet autodidact whose knowledge of writing came together with glue sticks and Mod Podge becomes dubious when you get to the doctorate level of higher education. That being said, before I deep-dive into diarism, I’d like to say that what I appreciate about spaces like Writing Excuses (the podcast) is that they provide a free type of education.

There are many types of educations when it comes to creative writing, but what feels important to me is to have opportunities that exist outside the academy and outside monetary obligation. Not to mention that—good grief—there are entire swaths of the academy that still hold prejudices against genre fiction existing inside the workshop. What remains for those writing in speculative and fantastic styles means trying to get into competitive (and also expensive) alternative workshops like Clarion, Odyssey, Taos Toolbox, Viable Paradise, et cetera.

So anyway, what I am trying to say is that Writing Excuses is fabulous—and not just because they paid for me to get three square meals each day for a week on one of their retreats—but because they are luminous folks who uphold what I value: community, sharing, transparency, and cost-free writing advice.

No, this isn’t a sponsored post—I really just enjoyed my experience that much.

When I do these newsletters, I sometimes see you, the readers, as various constellations who might not always overlap: the small press fiction writers; the poets; the speculative fic writers; the traditionally published ‘Big Five’ crew; the readers in general; visual artists, friends from my life, people who found me on Reddit… I try to create some aperture where whatever I’m touching upon could be applied to your life at some level. What I want to talk about today is fandom and what we can learn from it. To get there, let’s do a little scene-setting:

I’ve written about this before, but for about a solid 10 years I identified solely as a poet. I mean, in my heart, I am still a poet, but I am under no illusion that I will ever be a widely read or celebrated poet. I published one slim volume of experimental poetry, and if that’s the only book of poetry I ever put into the world, I can die satisfied with that. No mourning; just vibes.

But despite feeling like a bit of an outsider to the world of poetry at the moment, I can still tell you a lot about how poetry operates (what we cheekily refer to as “Po’ Biz”). There are a few ultra-rare poets whose work seems to penetrate a pop cultural sphere where they seem almost entirely removed of from the business of poetry (Rupi Kaur, Amanda Gormon, Amanda Lovelace…), but for the other 99.99% of poets, there is a business of prestige because there is no other type of business. Poetry doesn’t sell, as the age-old adage goes.

What this translates to… is that there is an entire world of literary culture out there that hungers for external validation through cachet and prominence as a means to sustain itself. As liberating as it can be to feel like "well no one reads poetry so in a way I am free from the b.s. of publishing" it also, from another angle, creates a type of crabs-in-a-bucket quandary. As a poet, agents generally don't represent you. If you publish, generally no one will read you except for other poets. So how do you find your readers? Often, a poet will apply for pre-publication awards through a university, non-profit, small press… and if they win, their book gets published. Winning an award that leads to a book is how most poets begin to form a name for themselves.

Beyond poetry, there are also swaths of the literary fiction and nonfiction worlds where there are obsessions with who are publishing widely enough to free themselves of the 'only poets read poetry' type of culture. It becomes about who is getting NEA grants and other fellowships with sexy cash awards; who is getting writer residencies and reading slots at AWP and universities; who is getting their books placed on the syllabi of classes at elite institutions….

If I have any misgivings about my time spent trying to launch some sort of career as a poet or fiction writer—is that I’ve often vied for prestige because that is what I thought I was supposed to do—because that is what the culture taught me was valuable. I would publish a story or a poem in a print journal that is attached to a well-regarded university with a well-regarded MFA program—and then what? Does anyone actually subscribe to those journals? I wanted to reach other humans. I wanted people to read my work. I’m not sure I’ve fully succeeded there, even with two books now under my belt. On some days, I wonder if some of the favorite stories I’ve written were even read by more than a dozen people.

If I could talk to a younger me, I would offer them up the advice that trying to find readers and connect to them is more important than trying to impress peers with bylines.

Another bit of advice I would offer to a younger writer is to not be scared of friends publishing you. If you have a friend who enjoys your creative work and wants to publish you, that’s literally just community-building! I used to be so averse to being seen as some cronyist networker (I think I developed a certain repulsion to “networking” from my time living in New York), that I would run in the opposite direction if I even sensed that something good might happen because someone just liked me and wanted to lift my work up. These days, there are more important ethical quandaries I’d rather worry about and spend my time on.

I’m giving myself some grace though, because as much as some of us crave our work finding its readers, I don’t think just because we possess hindsight as a type of wisdom that the timeline would have played out any differently. It’s possible in another universe I said yes to every opportunity and exist exactly as I am now. Same goes for you. So, if you’re also starting to be hard on yourself about missed opportunities, perhaps you should give yourself some grace as well.

That all being said, I want to just relay a story that was told to me as a sort of parable on the virtues of fandom as a type of community-building…

There is a writer (we’ll just call her Karlova); I originally met Karlova about a decade ago through an event she did in a place that I lived. I became fascinated with her because it seemed she was a rare individual who moved between science fiction conventions and small-press poetry spaces and many other worlds that felt both familiar and far apart to me. I don’t think it would be too controversial to say that most readers find their genre or subculture of choice and stick with them—so I was intrigued she had multiple homes in multiple communities.

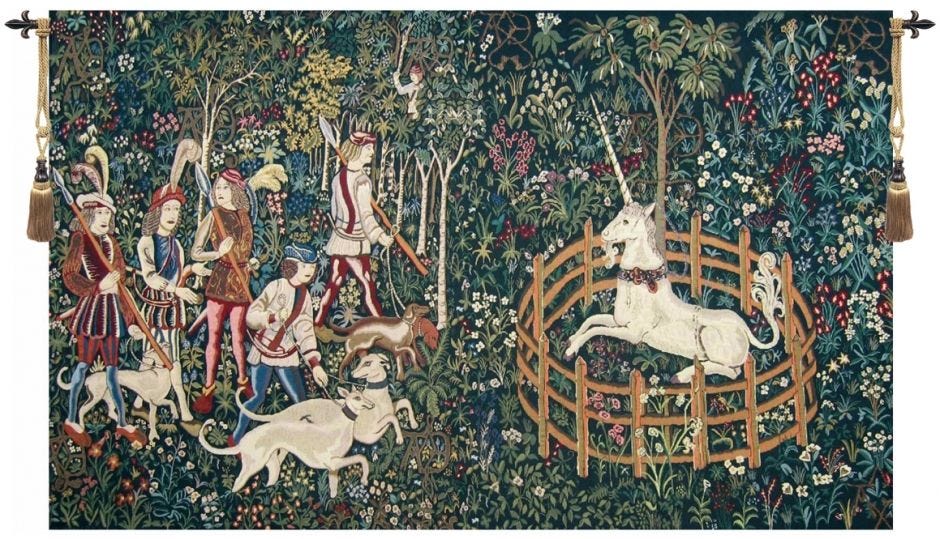

The conversation turned a bit to my perceived boundaries of publishing and readerships, and I essentially said something to the extent of that I am a geek at heart and would love to know more fandom inside literary culture, but because of my more experimental/lyrical style of writing I’ve always had a slight fear of being rejected in sci-fi spaces that value ‘invisible’ prose. I said those places aren’t for me. I then came up with an example of who I felt more seen by. We’ll keep using pseudonyms for now, but just imagine the type of writer who publishes exclusively in magazines like The New Yorker, but all of the stories contain a speculative—or fabulist—element. An elixir of eternal life. A sighting of a unicorn. The possibility that intelligent life exists. We’ll call this writer “Cleo.” Cleo publishes exclusively in literary fiction spaces, but nearly all of Cleo’s work is speculative. I said I like that Cleo can write in a literary-forward style but still use genre elemnts.

What Karlova said to me next is something that has stuck with me for nearly a decade now. She said that if Cleo chose instead to spend time going to cons instead of academic/literary spaces, she would be a household name in SFF and fans would be cosplaying as Cleo’s characters instead of focusing on her accolades. She wouldn’t be an unheard-of name in the fan world of science fiction—she would be part of it. What stuck with me is this theory that Cleo’s cachet in the literary world was her choice: not a destination she arrived at by the types of stories she wrote—which is what I had always believed.

Because the internet is the internet, I want to add the footnote that this isn’t particularly about Cleo herself—or Karlova even—or who the real people are. It’s about this idea that the reader spaces don’t necessarily find you; often it is you who finds the reader spaces and dedicates yourself to them.

One of my goals for this oncoming year is to spend more time inside fan spaces and sci-fi spaces in general. I don’t think it’s done me much good to be inside my own head and self-reject about who my creative writing is for. I’ve been spinning my wheels for the past few years about where I am and where I want to move forward as a writer (partially because I was trying to spend time on myself as a type of scholar), and something I’ve made peace with is that I need to be nurturing the work I’ve created and to stop downplaying it based on rigid ideas of creative communities.

During the Writing Excuses retreat, I decided to unpack a fantasy novel manuscript I began in 2017 and hid in a trunk because I thought it was too ‘literary’ for genre communities and too ‘genre’ for literary communities. And while I do think there is value to putting on the hat of the artist-statement-maker or the self-studying-scholar or the marketing-and-publicity-person… it can also be harmful to overanalyze one’s own work to the point of giving up on it or hiding it away.

I don’t want to get all woo-woo (because it is just coincidence, after all), but after I started finding a healthier attitude toward my creative output, I received a request to reprint a selkie story I wrote, a novelette that involves changelings was picked up after two years of rejections, and I’ve begun to reach out to both agents and literary journals again (I’m also trying to see if some of the Moonflower… stories can be republished to help find new readers). I also finished my first new piece of short fiction since the beginning of this year.

If there’s any takeaway, I suppose it’s that perhaps we could all be embracing fandom some more as a type of worldview. Part of this means being a fan of your own work—allowing yourself to geek out about what you’re doing. Too much worrying and vying about prestige and careers (which often does come along with financial obligation/expectation—let’s acknowledge that too) can also mean sitting inside displeasure for too long.

I don’t know if this actually means the work I’m excited about will find a home, or enter the world in a larger capacity, or even find the communities and fandoms I wish I could know more intimately… but trying to build a place inside earnestness and devotion feels preferable to me at the moment than the type of success that cynically relies on achievement and rank.

Perhaps, if you have been feeling down and putting too much pressure on yourself to attain a certain kind of success, then this may be an opportunity for you as well to try to learn how to become a lover and admirer and supporter of your own creative work again—or for the first time.

Until Next Time,

JD