Dear Friends,

Last night I saw Secret Mall Apartment, a documentary about eight artists who set up a domestic space in an unused nook of Providence Place mall back in 2003. The public art project was the brainchild of local artist Michael Townsend, who ultimately took the fall when the apartment was discovered by security in 2007 (Townsend received a “lifetime ban” that was finally removed this year in time for the film screenings). You may have heard this story before, as it’s become a bit of oft-repeated urban folklore.

The gist of the mall project is that it started as a type of artist bet about who could stay in Providence Place the longest without getting caught, and Townsend discovered the abandoned space (it was used to store leftover construction material) that they slept in. The ‘spend a week in the mall’ project shifted as it became a challenge to see how they could continue building up a domestic space in the mall (and sneaking entire couches past security and up a ladder). At one point, they even built a fake wall and a door for the mall apartment residents.

I should note, that in case you don’t know, I currently live in Providence—and the film screening took place at Showcase Cinemas inside Providence Place. We were watching the film within walking distance of where the secret mall apartment once was. That type of local resonance was obvious: every screening has been sold out. This was probably the most people I’ve seen in a screening at Showcase since Barbie came out in 2023. Most of the time when I go see a movie at the mall, the theater is lucky to get a dozen of us. Yeah, it’s a type of lightning in a bottle scenario, but it feels good to be galvanized by being near something that’s come full circle.

The documentary got under my skin a bit in unexpected ways and has been worming around in my brain. I expected the film to be more in the genre of pulling off a heist, but instead it was a complicated portrait of Townsend and creating art as an extension of your life—as well as a story of what spaces we’ve lost along the way (often due to gentrification). It asks us what it means to erase that boundary between daily life and the life of an artist.

I didn’t know going into the film that it would shake up some feeling of saudade in me. In the mid-aughts I was graduating high school and starting college. Before I shifted my entire artistic focus to creative writing, I was a photography student (my high school mostly consisted of magnet programs, and we had the biggest dark room in the city at the time). I had my mother’s old Minolta to shoot film with, and my first digital camera was a Canon PowerShot ELPH that I took literally everywhere with me. One of the most startling aspects of the doc for me was that Townsend had a similar small digital camera that could fit in an Altoids tin, and that he was always filming.

He actually had over twenty-five hours of his own footage that got interwoven into the doc itself, which… I can’t even explain how incredible it is that the footage of the mall project not only exists, but has survived nearly two decades. Something he said after the screening last night (both Townsend and the director, Jeremy Workman showed up for a Q&A) was that he never intended that footage to be seen by anyone. It made me think about the ways I once recorded my own life, simply because I could. I probably still have hundreds—if not thousands—of photographs from a similar era. But I never took them with the notion that they would be online. I was just existing in the moment of my youth.

The documentary unearthed a lot of complicated feelings and memories in me. It reminded me of a time when life was slower, and when I belonged to a more private world of art-making, one that was untouched by this awareness of an audience that social media has instilled in us. I sometimes wonder when I teach my students how they filter their own sense of self through TikTok, through YouTube, through Twitch. The world is different now that everyone has an HD camera built into their smartphones, and that we could all film or be filmed at any moment. Our phones are always connected to the internet. That sense of “being offline” has evaporated. As I get older, I’m beginning to see the generational gaps become more defined, or at least acknowledge that I lack the imagination to know what it would have been like to grow up in a world where platforms like Facebook always seemed to have existed. At the same time, I am trying to close the gap, to understand what makes me different from Gen Z or Gen Alpha. I want to learn a pidgin language to speak between us.

I tend to think about technology often as a distinction. I didn’t grow up with a computer. My family didn’t have the money, at least not until I was approaching middle school, and my family was finally approaching something closer to middle class (at least until the Recession made them poor again). The documentary made me think about how being online and offline were such distinctions for me for the first two decades of my life. Online involved a dial-up modem with its screeches and beeps. It was something that was done with intention, with a sense of ritual. Even when I got on cable internet in high school, there was a distinct feeling of logging on. I logged onto AIM. I logged onto LiveJournal. There were ceremonies to logging off, to feeling like you were leaving the digital world for a moment.

When I wasn’t set up in front of a PC, I was offline, and life was slower, surrounded with mysteries. Some of these mysteries were solved by carrying a camera around that did not live inside your phone.

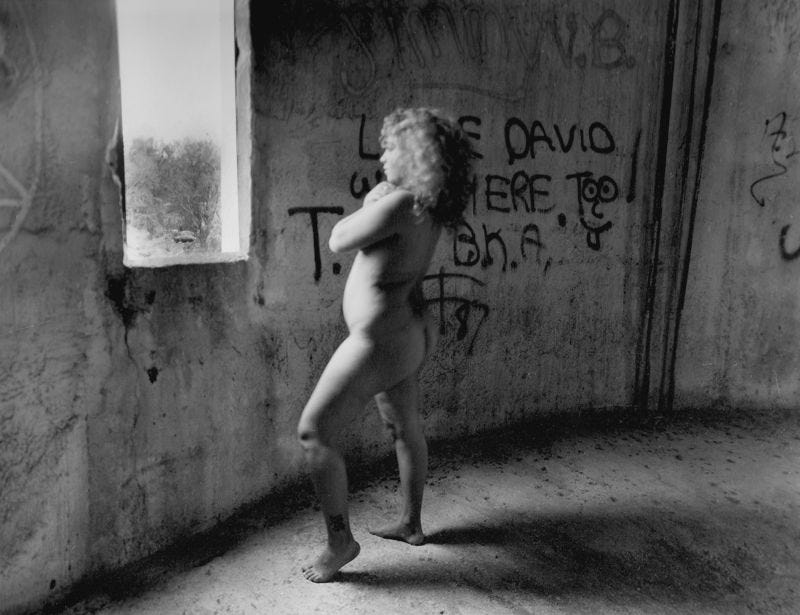

I’ve only been in Providence since 2021, but I did grow up in an urban part of Florida with its own stretch of suburbs between swamps, industrial cigar factories turned into nightclubs, too-many shopping malls, endless strip malls, and a dead downtown full of empty skyscrapers. As a photography student, I was into “urban exploring,” and often broke into abandoned buildings to take photographs. I should note that one thing that I appreciate about the documentary and will also acknowledge about my own life is there is certainly a shield of white privilege that goes into being able to “break into” public spaces and be given the benefit of the doubt if you are caught.

I never had a secret mall apartment, but I remember countless trips to the mall just to get out of the heat and into the air-conditioning. I remember doing fashion photo shoots in a Home Depot, posing my models behind model doors. We used to sneak out in the middle of the night to go to the smoking sections of diners—or else wander the too-bright aisles during the graveyard shift of Walmart. We made do with the sea of chain stores we grew up around. I knew young artists around my age, but often we had to find a path to art surrounded by conglomerates in the city and the suburbs.

What the documentary made me miss and yearn for is a moment of my life when I was young and connected to other artists, and how we felt like we had all the time in the world to figure out who we would become. We were young and bored and reckless and bold. We hadn’t fully been stolen away yet by notions of careers or adulthood. We made art where we could. My friends and I desperately wanted to grow up and get out of Florida, but we also had this perverse drive to inhabit and make sense of the landscape that was our home. We were the type of youths who would have built a secret apartment in a mall if the opportunity had presented itself.

It’s hard to put into words exactly what the documentary shook up in me, but I would say part of it is about wondering how to keep the id inside us thriving—that child-like, instinctual need to make art for art’s sake. I don’t mean to suggest that anyone can fully resist a type of professionalization or that professionalization is even a bad thing. I think the longer you spend in the art world or writing world, you begin to figure out how galleries or museums or publishing houses operate. You learn how the sausage is made. I don’t think these urges and knowledges need to be at odds, but sometimes I do personally wonder how much my light has been dimmed by concerning myself with things like agents and publishing and literary magazines and reading series and fellowships and residencies and yada-yada. Have I lost some sense of myself that I used to go to Kinko’s at 1AM and Xerox hand-made copies of poetry chapbooks? Does part of getting older mean you outgrow being the type of person who would camp out in a mall for a week?

Part of me has also begun to wonder what community means in a post-2020 world. Do you still have the same sense of community that you used to? I definitely used to feel more interconnected with other writers in the early 2010s—both offline and online. I used to feel more compelled to go to conferences like AWP (The Association of Writers & Writing Programs), take part in public readings, publish in journals… I also remember some incredible discussion threads about writing community and publishing taking place on people’s Facebook posts. I’ve already talked about enshittification, but I’m not entirely sure changes in social media are to blame. I think one aspect of it is that a lot of my peers have either moved on to more-established writing careers—or stepped away from writing entirely. Maybe getting older is enough of an answer. I’ve been doing this whole “creative writer journey” for twenty years now. I suppose it would be weirder if nothing had changed.

Almost none of my friends are in their twenties any more, and a lot of my peers are entering their forties. I was just texting a writing friend last night about how AWP is having its annual bookfair this week in Los Angeles, and how I don’t have the same relationship with it anymore. I used to live for the pop-up offsite readings that sprung up around the different cities this conference would travel to from year to year. There was a time when I went six years in a row, and now even conferences feel like a part of a chapter of my life that has closed.

Maybe I’m just depressed. Or maybe I’m approaching my mid-life crisis. Or maybe this is the plight of the emerged-but-not-yet-established writer. Or maybe I’ve just been in a PhD program too long and have begun missing a writing life I once had. It’s possible that “all of the above” is the answer. I think it’s smart to be skeptical of nostalgia. It’s important to acknowledge that some experiences just change with age. I also think it’s important to know which experiences are individualistic rather than trying to tie them to generations or some other zeitgeist. I know this letter is more of an essay, and a personal one at that. But I believe it can also be some sort of important step of checking in with yourself to ask if you’ve somehow gone on auto-pilot. If you’ve somehow lost a sense of the magic and wonder that you once had. Hopefully that’s not just a question solely for me.

One last tidbit I will tell you about that feels more objective than subjective is that so many of our artist space and DIY spaces and affordable living spaces are gone. With Secret Mall Apartment, one of the aspects that the documentary covered was that an initial antipathy toward Providence Place mall had to do with old buildings being razed to the ground to set up space for expensive chain stores. The doc spends a good deal of time talking about Fort Thunder, a DIY/art-collective space in Providence that existed from 1995-2001 before developers kicked everyone out and tore the warehouses in Eagle Square to the ground.

One other thing this documentary stirred up in me was this question of whether financial insecurity and poverty has altered some sense of my artistic self (and other people in my generation). So much of my energy the past eight years has been focused on novel-writing and trying to create something that could be sold to a Big Five publisher. I’d be lying if I said a cash advance wasn’t one of my biggest motivators for pursuing traditional publishing. Similarly, I’d be lying if I said one of my biggest motivators in going back to school a final time wasn’t to make myself a more competitive teaching candidate for the academic job market. And part of what I’ve been wondering is what the teenage version of me who took photos in abandoned buildings and made DIY chapbooks at Kinko’s would think of all the things I’ve potentially had to prioritize in my life out of a hope for financial security being fulfilled.

I’m slightly too young for the hey-day of spaces like Fort Thunder, but I was fortunate enough to go to a lot of house shows in the early-to-mid aughts—and spend some time in DIY art spaces in the late aughts after I moved to NYC; although it was always clear these spaces had an expiration date. In late 2009 I moved from Bushwick to South Williamsburg, living on Broadway next to the Hewes stop off the J (the M train wouldn’t reroute there for another year). We had three people living in an apartment that was approximately 400 square feet. Needless to say, I spent as much time in my early twenties out and about in the city, walking around my neighborhood. I remember at the time having this understanding that gentrification had occurred and would continue to occur in Williamsburg (although more in the North part)—and that the artist-run neighborhood that Gen X friends once talked about was long gone. However, due to do the subprime mortgage crisis that had begun in 2007, any new construction has been paused.

I spent a lot of time down by the water off of Kent Avenue. The steel skeletons of massive high-rises that would block the view of the water were frozen with the Recession. The Domino Sugar Factory still existed. I went to a lot of poetry readings and shows and parties at places like Death by Audio, 285 Kent, Gowanus Ballroom, Proteus Gowanus, Rubulad, The Schoolhouse, Shea Stadium, and Silent Barn. I don’t think any of the spaces I just listed still exist, by the way, at least not in the same capacity as they once did. If any space wasn’t pushed out and destroyed by the existing housing crisis, surely most of these spaced were offed in 2020 during the Pandemic.

When I talk about these spaces: I’m talking about corn mazes made of mattresses, raves, costume parties, all-ages punk shows, wrestling matches, chiptune shows, themed poetry readings, graffiti on the walls, public art installations… and spaces where artists live with each other and bounce ideas off of one another in a community. Some of these spaces weren’t just event spaces, but homes for artists who put on events in their shared living spaces.

Back in 2018 I did an artist residency at a space in North Williamsburg owned by an artist-writer couple who bought into a building the eighties. I had only been gone from the city for four years at that point, and I couldn’t believe how much was already changed or gone. I understood that by the time I had moved to Brooklyn that most of the artist studios and spaces had been pushed out further east. It was clear though, as I walked by Whole Foods and nannies pushing kids around that whatever formaldehyde the neighborhood I once knew was preserved in had been dumped out. This is less of a conversation about when neighborhoods were “cool” or “relevant” or “authentic artist spaces” or whatever, but more-so about how quickly these areas have changed to house the extremely wealthy and primarily white. I honestly don’t know how anyone affords to live in New York anymore. I don’t know how young artists are making lives there. I barely made it work myself.

I can’t really express how important for me it was to have third spaces that were neither work nor home when I was younger. Especially third spaces that were free or affordable. When I talk about worrying that me and my students are beginning to speak a different language… it’s not just about navel-gazing or perceptions about generational gaps. It’s also a sense of outrage at what has been stolen from them. I can’t overstate the importance of artists being in community with each other in a way that does not rely on familial wealth or interactions with the State. Yeah, maybe these types of spaces are for the young, but at least the young should have an opportunity to still exist in these spaces.

I truly don’t how many of these spaces are left. The housing crisis continues. Rent is disgustingly high. Both Providence and my hometown of Tampa are considered “hot real estate markets” (ick), which means that people are really fucking struggling. About 60% of my own income as a graduate student living off a stipend goes to my rent. There’s not much left for anything else. I’m sure some personal anxieties this documentary also stirred up was questions of what an apartment or home is, and if I will ever own one.

So… yeah. That’s it. I’ve been lost in a type of yearning, wondering what’s been lost, what might never come again. What artistic and DIY spaces I barely was around for the tail end of are gone forever. If offline spaces are even valued anymore in the way they meant to much to me. How much aging changes you. How much professionalizing alters you. And also how many artist peers you have in your youth migrate away to other interests as you age. And most of all, just wondering how much I’ve changed since my days when I used to bring a camera everywhere and explore the urban landscape like the world was my oyster.

As a final note, all of the photographs here are silver gelatin prints that were taken by me. Four of the images were taken between my junior and senior year of high school at a pre-college program at SCAD. Coincidentally, in the documentary, it mentioned Townsend momentarily taught at RISD’s version of this type of program, and that a lot of the young artists who became part of the mall project were his former students. One note I loved from the doc is that all eight people who used the apartment have continued to work as artists or art educators. That’s quite rare indeed.

Until next time,

JD

Not sure if we’re the same age but I frequented a lot of those same DIY spaces in New York. I loved checking the Brooklyn Vegan blog to find any Death by Audio shows. I felt alive at those shows. Once they were squashed out, I moved back to Detroit where the DIY scene still exists but “property value” is making it much more, if not nearly impossible, than even 5 years ago. Feels like I woke up after the pandemic and DIY scenes were gone but we got protected bike lanes?? Wish we could have both ❤️