The Four Dyads of Building Fictional Worlds: Part II

Rounding out with play, work, the natural, and the supernatural

Dear Friends,

Last week I offered up a different perspective on the ways we discuss fiction-writing, its elemental components, who this fiction is for, and the rhetoric we use to connect to our audiences. More importantly, I also tried to communicate these ideas while emphasizing that writers make a complicated series of choices, and there should be more nuanced ways to discuss fiction without immediately relying on hierarchies based on taste.

Once again, here are the four main dyads I’ve identified:

The tradition–innovation dyad

The prosaic–poetic dyad

The play–work dyad

The natural–supernatural dyad

Previously, I spoke mostly of the tradition–innovation dyad and prosaic–poetic dyad. What I’d like to re-emphasize is that I’d like to think of each vector as part of a double helix: linked strands composed of complex molecules. Most of us don’t live entirely on one side or the other of each dyad. We are making small choices and accumulating a complex whole to fit our fiction-writing needs.

For a brief refresher, I’m thinking of “tradition–innovation” as the foundational (what some might call “structural”) elements of fiction, including character, plot, setting, and so on. My argument was that if you challenge or remove one of these traditional aspects of narrative, you run closer to creating an overall effect that is more innovative or experimental. Alternatively, if you adhere to it, you stick closer to foundations the average reader is most familiar with.

When it comes to “prosaic–poetic,” I was mostly talking about voice and style, which often comes from using poetic techniques in fiction. This sometimes comes down to talking about the musical quality of individual words and the sentence as a unit built up of words. On one end we have extremely stylized sentences that call attention to themselves (sometimes attributed as “purple prose,”) and on the other end we have “invisible prose” or “transparent prose,” which supposedly renders itself into a type of neutral voice that foregrounds other narrative elements (even this is debatable, as I believe that even the most “neutral”/“unlyrical” prose still has voice and style).

I’m here to take us home today and talk about the other two. One accessibility caveat I have to remind is that Substack doesn’t seem to really have the functionality built-in to create tables, so I’m using screenshots of a Google Sheet for each section below. If you’d like to view the dyad sheets (which you might, as the text in the screenshots below appear very tiny!), I’m including a link here.

This one is going to get a little thorny, so bear with me. The simplest way to boil this down is: these are the choices that the writer (consciously or unconsciously) makes when interfacing with the reader. Specifically, these are the choices on how much to let the reader play in the storyworld versus how much to make reader work during their visit. There are other ways to frame this too: giving the reader a satisfying experience vs. perturbing them; letting them stay complacent vs. challenging them; entertaining them vs. boring them; attending to them vs. transgressing them.

There are a few different angles to approach this from. On the “play” side we have:

Borrows or replicates narrative elements from popular genres (e.g.: physical action scenes from action/adventure; an unsolved murder that isn’t revealed until the final few pages from mystery; traditional love interests from romance…) in order to hook the reader in and keep them entertained.

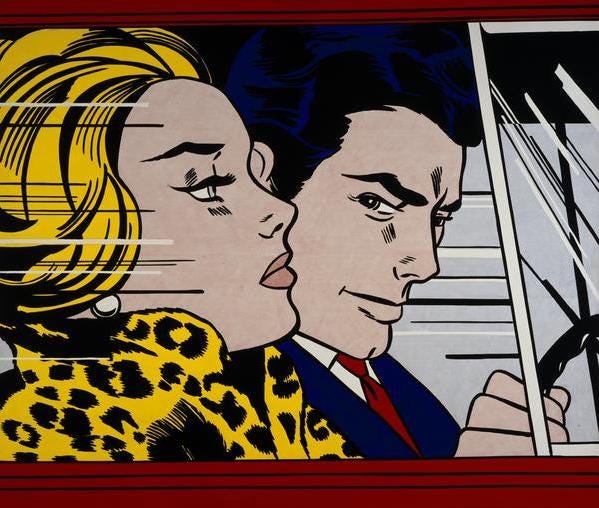

Gestures toward other forms of entertainment (e.g.: movies, television, comics) or aspects of pop culture (e.g.: current popular trends).

The norms of society are represented in a way that does not challenge the status quo. This could include sexuality, gender, race, class, etc.

Tries to create an enjoyable, satisfying experience for the reader (e.g.: the ending is a happy one).

The “work” side involves transgressing notions of what is normative, popular, mass culture, etc. These are challenging the reader’s comfort level and values. You may think me a cynic for saying this, but when one’s work is situated entirely in “play,” the over-all effect is a capitalist one (because it’s those books that indulge all of the reader’s whims that keeps the publishing industry afloat).

Fiction-as-entertainment is the vector that makes money for Big Five publishers—and to a lesser extent makes money for individual authors too. There is more of a financial investment in pleasure and relish than there is in displeasure and disgust. I don’t think it’s too controversial to say that, no? You don’t crowdfund $41 million dollars off Finnegans Wake.

Here’s the more controversial part: there has been a lot invested in the status quo’s relationship to entertainment. In terms of character, it’s the reason the white, abled, cisgender, middle-class, monogamous heterosexual couple who makes beautiful love (for procreational purposes only!) is considered the norm. The status quo is generally only interested in the minority when money can be made off the minority. It’s the reason Walmart can sell Pride- and Juneteenth-flavored ice cream while keeping its boot on the necks of working class Black and/or LGBTQ+ peoples its employs.

I know talk of economic + political systems & identity politics makes some of you itchy, but I always like to remind people there is no “default” in fiction-writing. Everything is a choice, and often when we make choices we are asking to consider what is popular, what is over-represented, and what sells. We can’t remove capitalism without talking about other “interlocking systems of domination”—bell hooks said as much. These systems cannot be extricated from one another. Which is the reason that why when I talk about entertaining the reader, I feel a natural compulsion to also consider entertainment’s relationship to capitalism and the publishing industry.

You’re overthinking things, again, JD, is something you might say. I’m not considering capitalism and the publishing industry when I write my little stories. Yes, of course, we can say that everything a writer creates happens in a laboratory, but the laboratory does not exist in a timeless, cultureless vacuum—and publishing doesn’t either. If you’re writing a dystopian novel in the 2020s, you can’t pretend like you’re unaware that The Hunger Games exists or that Hulu turned Atwood’s famous dystopian novel into a television series. The publishing industry certain is going to consider whether the trends of dystopian fiction have come or gone or are ready for a new cycle when they decide to publish or pass on your manuscript.

Let’s also talk about the topic of entertaining the reader (or allowing them to play in your worlds) from another position that will probably be a little less contentious. Pleasure, familiarity, entertainment, and play are all powerful strategies that we all have access to. One of my favorite short novels of all time (We Have Always Lived in the Castle by Shirley Jackson) starts off with a murder mystery that isn’t answered until the final chapters. I’d argue that the novel ultimately subverts the murder mystery plot, but that’s a conversation for another time, and right now I’d like to draw your attention to how the opening paragraph pulls the reader in:

My name is Mary Katherine Blackwood. I am eighteen years old, and I live with my sister Constance. I have often thought that with any luck at all I could have been born a werewolf, because the two middle fingers on both my hands are the same length, but I have had to be content with what I had. I dislike washing myself, and dogs, and noise. I like my sister Constance, and Richard Plantagenet, and Amanita phalloides, the deathcup mushroom. Everyone else in my family is dead.

From the first paragraph, we understand there is something unusual about Mary Katherine (AKA Merricat). I’d say this is where there can be some overlap between tradition–innovation and play–work. Merricat is a character that makes the reader work to comprehend her worldview. The murder mystery keeps the reader in play. At the same time, even though there is something entertaining being engaged with a delicious murder mystery involving arsenic, Jackson is also keenly subverting gender, sexuality, and traditional ideas of the family unit in WASP-y New England. It’s the poison plot that I’d wager convinces most of the readers to go deeper into Merricat’s rancorous and destructive world.

I’m not asking us to overthink how much we entertain or disdain our readers to make us all distraught. I’m sure plenty of authors write novels about werewolves because they just like werewolves, and they’re not really considering marketing trends—even in their heart if they think yes I love werewolves werewolves are fun and awesome woof. I’d imagine a good deal of literary fiction writers wax on about beauty and betrayal and death and love without thinking too deeply about those themes either. Our day-to-day lives are full of death and love, and those two topics are often unavoidable in fictive worlds. Being aware of how you’re connecting to the masses is not a bad thing. The more idealized and romanticized your notions of these concepts (or themes) are, the more likely you will be connecting to a wider audience and readership. It’s good to know these things—to use them to your advantage. As I suggested, I’m certain many people operate this machinery already because it lives in their subconscious from all the popular fiction they’ve read over the course of their lives.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Darcy and Elizabeth's relationship has become a model for a type of sweet, true love (after they overcome their titular hubrises). This has become a model for many writers’ ideas about love. Alternatively, Georges Bataille’s L'histoire de l'œil involves a woman removing a priest’s eye (after killing him, of course) and inserting it into her vagina. There’s probably not a lot of contemporary Bataille remixes out there for the reason reason most people wouldn’t be talking about Bataille at their church bake sale. The taboo operates in a different space from the norm (I think of Gayle Rubin’s ‘Charmed Circle’ here). That being said, it can be as exciting as it is alienating. Shock value has potential to toy with our emotions in ways we might not normally experience feelings.

Familiarity and comfort has its own draw too. I’d wager that most of us would rather read a Calvin and Hobbes anthology over Butler’s Gender Trouble if given the choice. Popular tropes and entertainment can be ensorcelling. Discomfort can also cut us deep, giving us readers unrest even after the book has concluded. It’s up to you to choose what lineages you’re working in.

Even though I’m prattling on in extremes, few books exist on polar opposites of the play–work spectrum. Sure, I bet we could all go into a used book store and find a mass market romance paperback (oiled abs and torn bodice on the cover!) that nicely fits entirely with the left column—or alternatively some avant garde book from Fiction Collective Two (FC2) or Semiotext(e) that leans to all the extremities of the right side. For the rest of us, it is a ratio and we exist somewhere in the middle.

What I want to remind everyone is that we all have the capacity to make choices to pacify the reader and their worldview or challenge them. These ideas are not mutually exclusive. You can have an action-packed fight scene and teach the reader something about ableism. You can have promiscuous sex with a green, avocado-loving sea monster and have an exhilarating car chase at the end of the novel. Asking yourself to figure out the ratio of just how much your reader plays or works in your storyworld can be a powerful craft tool.

Ah, now we get to the talk of magic and science and reality and fantasy. My favorite.

So much has been said the topic of the natural world vs. the supernatural world in fiction. There have been endless debates about “literary fiction” (which itself is a genre) vs. “genre fiction” (which includes many subgenres). There have been arguments that show how “literary writers” from Colson Whitehead and Toni Morrison to Karen Russell and Carmen Maria Machado destabilize categories by using elements from “both sides,” thus rendering the walls of genre meaningless. There are more subcategories (dark fantasy, weird fiction, magical realism, slipstream, fabulism, irrealism, surrealism…) of speculative/fantastic fiction than we can shake a stick at. A couple of years ago, Lincoln Michel used the “political compass” model to try to map genre on an X-Y axis that includes naturalistic, expressionist, mimetic, and fantastic—a model I thought was fabulous because it illustrates just how complex we can make these distinctions.

This is all to say the discussion of the fantastic next to the realistic is a very, very, very well-mapped terrain. The discourses have been discoursed. But it also highlights that an integral part of fiction-making is asking ourselves how much we imitate our lived experiences and our known world into the storyworlds we create.

To be honest (speaking of the complexity of these discursive elements), I even thought about trying to make a fifth dyad separating the generally accepted “laws of nature” from task of replicating one’s reality in fiction. Because at the end of the day, we all, for example, probably can agree that we live on Earth, and on Earth we experience something we call gravity. We also all agree time moves chronologically, right? We all can’t agree what happens to our minds (or spirits—if you believe such a thing exists) after we die. We can’t all agree whether angels exist or not. And so on and so forth. Nature is objective; reality is subjective. Right?

But do we all agree in gravity and chronological time? With the flat-Earth theory out there and everything, I’m not even sure we can all agree we live on the same Earth. Which is to say this all becomes quite a bit muddled because to agree on “the natural” or “the real” we’d first have to agree on what mimesis (or, replicating one’s own reality into a fictional world) means, and we all don’t universally experience “nature” or “reality” the same way, so why not just throw them all together into one umbrella dyad? It feels entirely part of human experience to imagine where life came from, imagine what creature lives in the unseen darkness thousands of miles below the ocean’s surface, imagine who or what made the stars…. These are our ancestors: the first story-tellers. The ones we descend from. So it also seems important to track how we map reality vs. irreality/surreality and how we map the known vs. the unknown in our storyworlds.

Funny enough, this seems like the dyad I could talk about and write about for hours with all its various nuances and hypotheses, which is also the same reason I want this touch-down to be both brief and open-ended. In essence, this is the part of crafting fiction where we’re asked on just how much we replicate the reality we experience into the storyworlds we create—and how much we interject “what if?” into those moments of the unknown. How much we turn to myths and fairy tales and parables and the first stories we were ever told. We ask ourselves questions and we answer them in our fiction. Our imaginations fill in the gaps. It’s just that simple, right?

We are each being tasked to map complex choices in each storyworld we imagine.

Are we creating narratives, and if so, which familiar structural choices are we utilizing, altering, abandoning?

What voice are we taking on when we create this worlds and what style are we selecting when doing so?

What is our relationship to our reader (and ultimately publishing at large) and how much do we satisfy our audience—transgress them, challenge them?

How are we replicating the reality we experience as individuals (or as a collective) into fictive worlds—and how-much of the known and unknown universe do we place there too?

If taste comes in anywhere, it’s perhaps should be at how well we succeed at what we set out to do. Putting a vampire in a story; or writing a divorce plot featuring a wealthy heterosexual couple; or deciding to abolish setting and have your novel take place in a blankspace; or writing in a hyper-minimalist style with zero adverbs… isn’t inherently good or bad. They’re neutral choices.

Hell, let’s throw all the examples together. Writing a novel about two heterosexual vampires getting a divorce after spending the last six hundred years together in blankspace setting with hyper-minimalist prose isn’t good or bad either. That could be a generative prompt. We could get 100 of us to write that same story, but it’s not going to be the story, right? One of those novels is going to be the best one I read, which is going to be different from the best one you read. Those are the slippery, more intangible parts—even if we strive to speak of the flavors. That’s how we try to translate the magic into a tongue we can communicate from.

For now, I’ve given you an offering: four dyads, and hopefully a myriad of angles to approach your own fictions as well as the fictions of others from. If anything, this is an exercise in mindfulness—to create fictions with an acute awareness of the immeasurable choices you could make.

Too often we talk about the tree, its branches—which one grows highest—its leaves basking in full sunlight. For now, I’d ask you to slide into the dark soil beneath the earth with all the infinite roots growing this way and that: the thousand-and-one decisions we pull from our subterranean imaginations to bring our stories to life. It’s a little more mysterious, and a little more complex, and a little more scary—but also a great deal more exciting, no?

Until next time,

JD

Wonderfully thought-provoking as usual!