Creating Regional Gothic Fiction

or, an aesthetic for every U.S. region

Dear Friends,

Did I mention I passed my comprehensive exams for my PhD studies? You might see me a little more often this summer because it feels like I’m entirely back on my own time for the first moment in a while (it feels weird to be sending another letter just days apart when I usually write one per month). I completed my oral exams a couple of weeks ago, which has officially wrapped up the doctoral exam process for me. I wish I could say I’m “ABD” (All-But-Dissertation), but technically I have to defend a dissertation prospectus this fall before I can officially claim that title. I did change my email signature from “PhD Student” to “PhD Candidate” as a little treat though (whether that’s wholly accurate or not).

I ultimately wrote four fifteen-page essays during my exams, and at least three of them seem salvageable to do something with besides hiding them in a drawer for all of eternity. I have to admit, though, I’m intimidated by the scholarly publication process, which I’ve never approached. In terms of my own reading interests, I tend to gravitate toward publishers that put out creative nonfiction books that have a scholarly thread running through them; by this I mean writing that feels more centered in “creative writing” than “academic writing,” yet still engages with critical theory, philosophy, activist thought…. I find that hybridity and willingness to approach scholarly work through lyricism and experimental writing makes for more enticing and stimulating reads. Some presses that come to my mind who publish such work are Semiotext(e), AK Press, Zone Books, Sarah McCarry’s Guillotine, Action Books, Noemi, Verso Books, Ugly Duckling Presse, Siglio Press, Nightboat—just to name a few. While it will probably be a while before I feel brave enough to pull out my exam essays and revise them, I have been thinking more about where I’d like them to exist in the world—and which threads of thought I would like to continue to pursue.

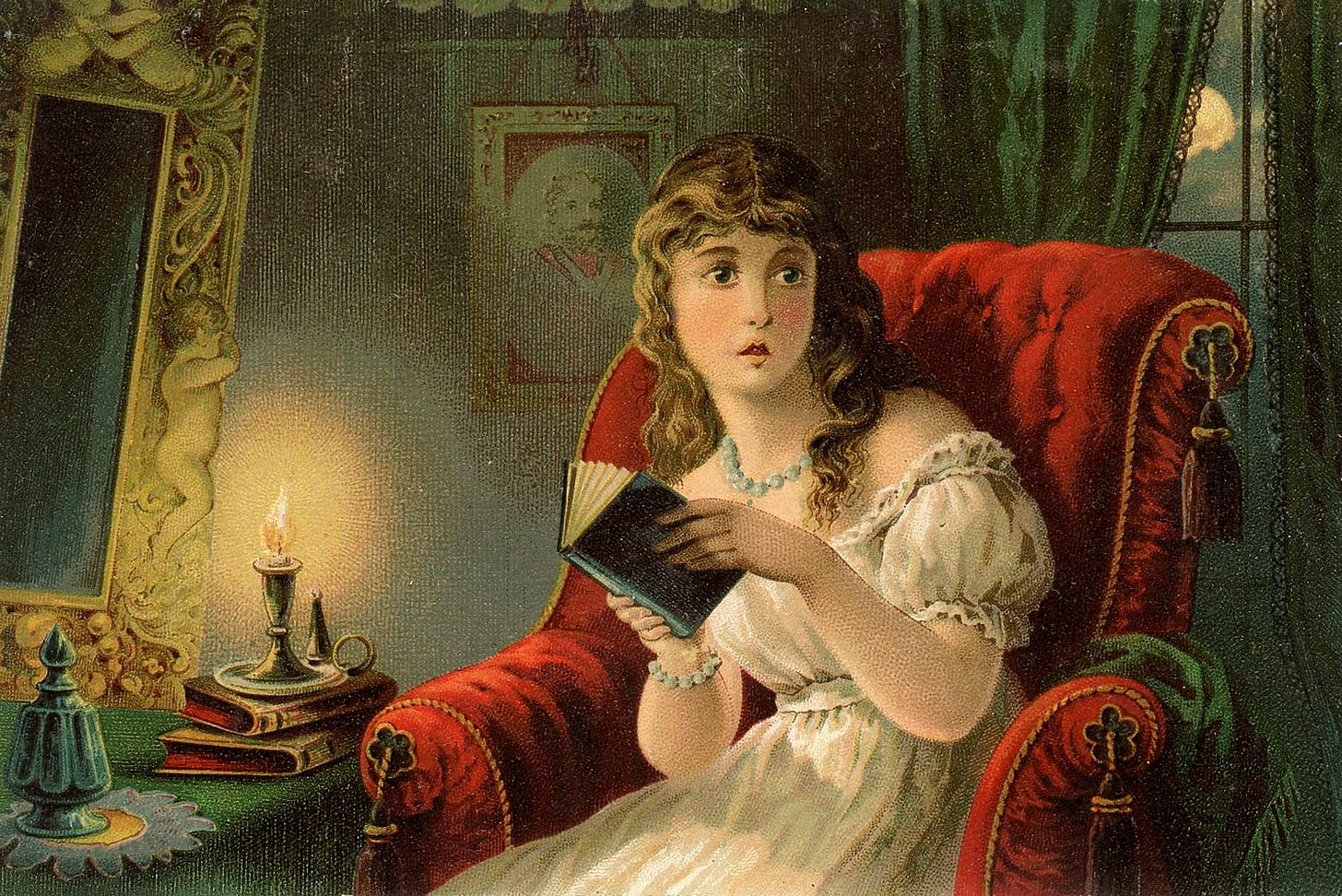

In my last newsletter I wrote about trying to create an inventory of your interests, and since I did that activity for myself, I’ve been mulling over my own inventory as of late. For one of my exam essays, I ended up writing about the Southern Gothic and contemporary Gothic fiction—a topic that also popped up in my interest inventory. If you’re not familiar with the Gothic, the easiest way to define it is a literary aesthetic connected to building an atmosphere through fear-based emotions and themes of being both literally and metaphorically haunted. You can also think of it as a genre, if you’d like, but it might be more helpful to think of it as aesthetic gestures that touch certain settings, characters, and plots. It also comes with many tropes and metaphors built in. Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto (1764) is generally cited as the literary blueprint. It wasn’t until 1935, when a Southern novelist named Ellen Glasgow was addressing a group of librarians in Virginia, that the term “Southern Gothic” was first uttered1. Glasgow coined the term when trying to draw a connection between her contemporaries like William Faulkner and writers of the past like Poe. I would be remiss not to mention that in both cases, “Gothic” and “Southern Gothic” were originally intended to be pejoratives. However, this connection opened up a space for additional mappings between region and literary aesthetic. Now, we treat these terms as neutral descriptors of a type of aesthetic or subgenre.

Although I’m a Southerner (in some sense of the word) and do have some allegiance to the Southern Gothic, I do have to concede that it does take up quite a bit of the public imagination as far as regional Gothic aesthetics are concerned—arguably because it’s the one that is the subject of the most scholarship. As an interloper (in some sense of the word) here in New England, I’ve come to appreciate all of my current home’s cultural histories and how they relate to Gothic storytelling. Just off the top of my noggin, New England has Nathaniel Hawthorne, Shirley Jackson, Lovecraft, Stephen King, the city of Salem and its witch trials, and the Warrens and The Conjuring cinematic universe—just to name a few. Which means, in terms of characteristics and tropes, that New England comes equipped with the legacy of Puritanism, witchcraft, nautical narratives, cosmic horror, and beyond.

When I was mulling over my own inventory, I was thinking of regional Gothic aesthetics as a type of marriage between my own interests in highbrow (e.g.: critical theory, arthouse films, experimental writing, poetry, literary fiction…) and lowbrow (e.g.: internet memes, Tiki bars, comix and zines, fast food, game shows, pulp fiction…). To get us closer to what I am trying to say, let me start with something a little more highbrow. While preparing for my exams, I read Critical Insights: Southern Gothic Literature, a collection of essays on the genre. In one of the essays titled “Defining Southern Gothic,” Bridget M. Marshall writes about how the Southern Gothic swaps out the traditional Gothic’s castle with the plantation:

The Southern plantation also serves well as a replacement for the more traditional Gothic castle because of its symbolic reference to a fallen aristocracy. Much as decrepit castles allude to an earlier generation's fall from wealth and power, so the destitute state of the Southern plantation in the post-Civil War period refers to the history of the planter class and, indeed, of the American South more generally. The physical space of the plantation (like that of the castle) echoes the fallen nature of the inhabitants with its many rooms, once beautiful but now disintegrating. These buildings hearken back to a lost past; the fact that they will never be restored, but only continue to decay often motivates the offspring of the aristocratic class and serves as a visible punishment to the untamed and ultimately ruinous power of the earlier generation.

Something that’s often hard for me to turn off when reading articles like this is this instinct to reverse-engineer scholarship towards a site to generate creative writing. Something that stuck with me was this idea that the Gothic laid out a boiler plate of characteristics that the contemporary, regional Gothic could swap out based on its own geographic histories and mythologies. I asked myself: if the castle is transmuted into the plantation in the South, what would the castle look like in New England? The Southwest? The Pacific Northwest? Which brings me to the low culture (and I say this lovingly): Tumblr.

In the 2010s, there seemed to be an obsession with creating internet-informed subcultures that could be defined by aesthetic values, which in turn could be used to describe genres of music, visual art, fashion—and be actualized through countless Pinterest moodboards. I’m thinking of seapunk, witch house, vaporwave, health goth, and the like. Some of these microgenres or aesthetic movements happened organically, but I view others almost anthropologically: as these active collaborative folkloric creations that came through a mixture of worldbuilding, roleplaying, and the digital equivalent of telling ghost stories around the campfire. The internet is the uniting force here. These aesthetics are part of the same digital tapestry that Slenderman, the Backrooms, YouTube Poop, corecore, the SCP Foundation, and an online obsession with liminal spaces are.

In early 2015, there was a trend going around Tumblr to share stories or create memes about the Gothic as a regional aesthetic. I would say part of these original posts were located more in forms of sincerity mixed with satire: inside jokes toward the places Tumblr users came from or knew intimately. It didn’t necessarily come out of place of, say, a deep knowledge of literary criticism as it pertains to Gothic fiction. While those initial posts are over a decade old now, the oral history of them has been catalogued in the Aesthetics Wiki under the “Regional Gothic” entry. As a thought experiment, I wondered what it would look like to try to combine some of the academic rigor of dissecting the Gothic genre with the playfulness of these old Tumblr posts to try and tease out these narrative characteristics and how they shift from one region to the next.

One consideration though is how generally or specifically you want to map out different regions2. If we were to try to pare things down to the fewest (I mean, outside of the binary of “East Coast” and “West Coast”), I would say we could stick to four regions: the North, the South, the West, and the Midwest. If we leaned toward the specific, we could certainly even hone in on individual cities: places like New York City, Miami, Detroit, and Los Angeles are rich enough to have their own variations. However, it would be an act of madness to run towards specificity, despite my background as a Floridian and my strong opinions that Florida is made up of three distinct regions3.

For this exercise’s purpose, I’ve settled on five regions: the Southern Gothic (combining the Deep South, Gulf Coast, Southern Florida, and Appalachia), the Northern Gothic (combining the Mid-Atlantic, the Northeast, New York City, and New England), the Midwestern Gothic (combining the Great Lakes, the Heartland, and the Great Plains), the Southwestern Gothic (combining the Southwest and West Coast), and the Northwestern Gothic (combining the Pacific Northwest with the Mountain West). There are an endless number of maps honing in on what makes regions distinct, but for my purposes I took my cues from a regional map made by Dr. Jeremy Posadas (which can be seen above). This is all a vast oversimplification, yes, but it will serve its purpose.

My next task was to think of elements of Gothic fiction that can be distilled and transposed to other regions. For our purposes, I’m using “Gothic fiction” in a looser sense, and not necessarily trying to distinguish between “Gothic horror” and “Gothic romance.”4 I’m also collapsing 18th century and 19th century texts together to act as a stand-in for “The [Original] Gothic.” Most of the regional Gothic media comes from the 20th century and after anyway, with a few exceptions who do feel tied to their regional connections (e.g.: Hawthorne). Ultimately, I settled on six different categories that can be adapted across geographic regions:

“The Castle” — important settings and architectural references

“The Image” — sensory details that build atmosphere, a sense of mystery, suspense, and often act as a metonym for the emotional landscape of the narrative itself

“Decay, Destitution, and Isolation” — while Gothic fiction tends to have dilapidated settings and characters in isolation, what this actually looks like can change from region to region

“Stock Characters” — in the Gothic, these might look like a woman in distress; a tyrannical husband; a governess…

“The Supernatural or Paranormal” — hauntings, ghosts, and revenants come first, but this could be expanded to include any non-spectral monster, religious or spiritual occurrence, mythological figure, or cryptozoological animal

“Tropes and Themes” — while this has some crossover with pretty much every aforementioned category, there are some common plot conventions and literary devices that wouldn’t necessarily fit into the other categories

I tried to look at existing media and not just rely on my own imagination/speculation, but I did have to fabulate a bit to fill in some gaps. I ended up creating an entire spreadsheet about these regional Gothic aesthetics, which can be found here. If you have any additions or suggestions, feel free to comment below. Also, if you have your own region (United States or otherwise), I’d love your contributions on what your Gothic regional subgenre would look like. I could tell you about the Florida Gothic, but I do think we must keep some things for ourselves.

As a caveat, I should note that even if I listed something as regional, a lot of these elements are across the board. Any monster could appear in any region. It would also be hard not to find a region that doesn’t, say, reconcile with the wounds of Christianity and evangelical trauma—or xenophobia and racism in all its manyfold incarnations. It would be hard to find contemporary Gothic fiction that doesn’t have a haunted house in the middle of nowhere or a crumbling cemetery nearby or a small town with an abandoned Main Street and a local conspiracy. Additionally, while this probably doesn’t need to be said, I did want to add that I was cataloguing in a way that doesn’t always have nuance, but please don’t take the spreadsheet as a carte blanche invitation to generate writing off of. In certain instances (e.g.: the Wendigo, which comes from the Algonquin peoples), you should probably consider the cultural and ethical responsibilities of inspiration and source materials. Lastly, documenting tropes doesn’t mean the tropes themselves aren’t problematic or that I am inviting use of those uncritically. I know, I know, I probably shouldn’t have to say any of this—but the internet does have a bad habit of opening up rather ungenerous readings from people—so consider this my CYA clause.

As a final thought: if you’re curious what my exam essay was about: I was playing with this idea that certain contemporary queer authors reject the narrative architecture of catharsis when working with the Gothic—often filtering their identities through the monstrous and “converting the genre’s climactic purge into an ongoing communal metabolism.” I focused on three Southern Gothic novelists for that essay, and hey, maybe one day it will appear as a published article. But for now, I’m going to focus on another Southern task: eating this biscuit and drinking this chicory coffee.

Until next time,

JD

Since I’m an American, I’ll just be sticking to regions in the United States here.

To oversimplify this: the Panhandle is part of the Gulf Coast and shares more with Mobile, Biloxi, and New Orleans; anything north of Ocala is part of the Deep South and has more in common with Georgia; anything from Central Florida down to Miami is part of its own unique Southern Florida region.

We could probably think of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre as creating a butterfly genre effect here that served as an ancestor to Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca. Hitchcock’s 1940 adaptation of Rebecca ushered in a cinematic Gothic romance subgenre. From there, an entire “Gothic romance” subgenre flourished.