On Mental Illness & Millennial Novels

Millennial fiction, therapeutic journal entries, and past selves meeting present ones

Dear Friends,

This past week I had a telehealth meeting to go over the results of a robust neurological/psychological evaluation. To be honest, I was mostly just curious if I was on the autism spectrum (inconclusive) and/or had adult ADHD (needs further testing). What did come out under the official "ICD-10 Diagnosis" subheading were the following:

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Persistent Depressive Disorder

Social Anxiety Disorder

Getting an official anxiety and depression diagnosis is a bit like living in a house for decades alongside a litter box, food bowl, scratching post, and mouse-shaped catnip toy—and someone suddenly announces to you, "You have a cat." And you're like, "Yeah. There were hints."

For what it’s worth, I have already received previous diagnoses from other professionals regarding anxiety, depression, and ADHD, so nothing feels different. I don’t know what doing the full test promises besides some hyper-real representation of the story I already knew inside my body. The test I took involved everything from filling out Scantron booklets to being quizzed on vocabulary words to having to recreate patterns with colorful dice to being asked to memorize strings of numbers and repeat them forward/backward. I don’t know if this changes much besides feeling officiated in some way. It’s like I’ve been wedded to my mental illnesses and executive dysfunctions so long, and this was just me picking up my marriage license from the county clerk’s office.

In any case, I think I partially just wanted the experience of doing the test as an adult. I like to collect experiences. If you asked me if I would like to try eating a century egg or sleep in an underwater hotel or participate in conducting a penguin census in Antarctica I would probably just say, “Okay.” It is the writer’s knack to build a cabinet of curiosities inside your heart.

At the bottom of the results document, there were some recommendations for moving toward mental wellness. One item recommended to me was keeping a journal, especially to track mood and sources of anxiety. I was like: okay, I can do that.

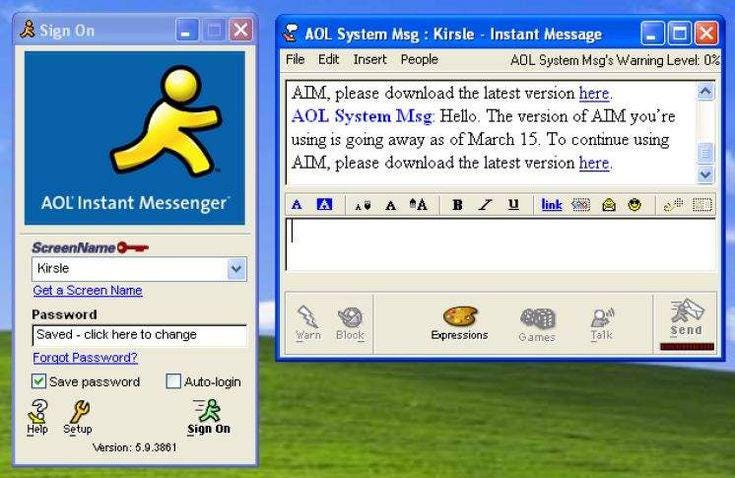

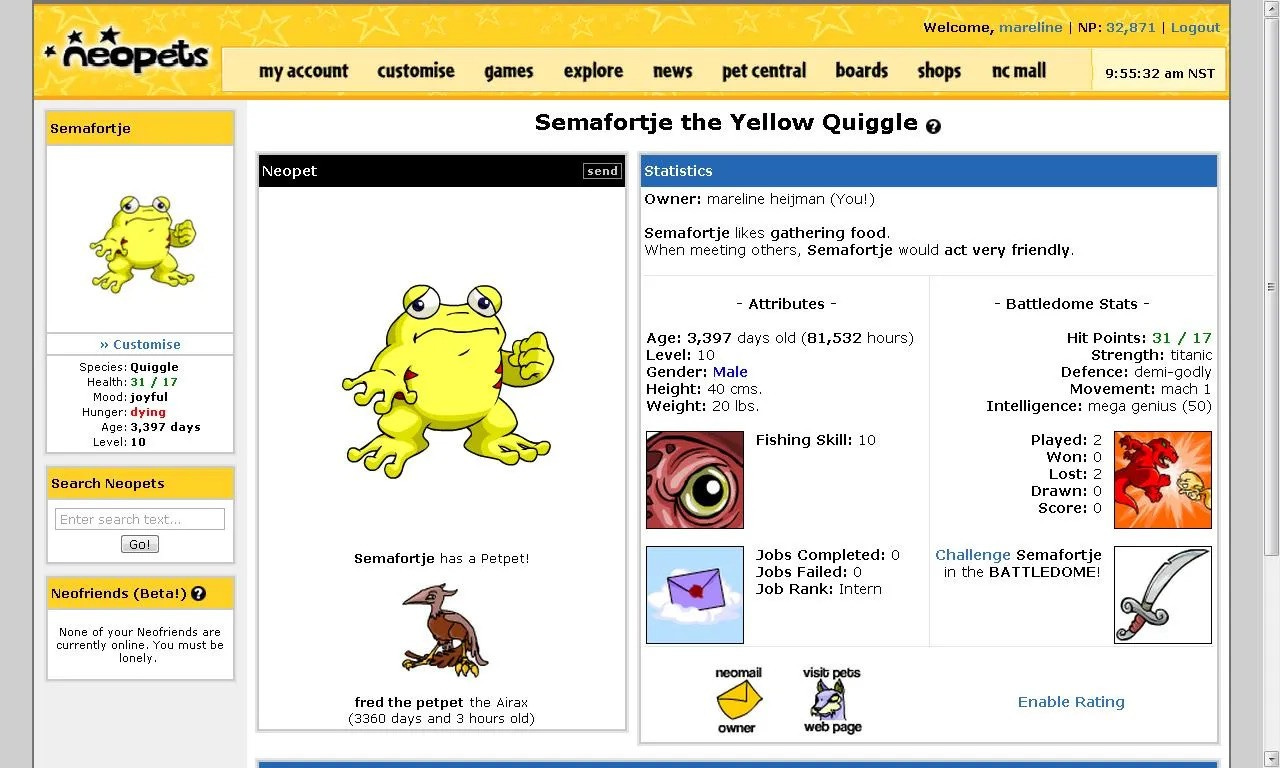

I’ve written a little about this before, but the odd thing is: I did this for nearly a decade between my teen years and early twenties. I journaled and blogged online almost daily. In a past life, there are hundreds if not thousands of journal entries penned by me. At some point, adult life took over, and I stopped journaling for fifteen years. It’s been surreal to think about putting a journal-writing practice together again. I feel like a former child actor from a Nickelodeon show auditioning for an A24 film. Like… maybe I had a propensity for this once, but it existed in a version of myself that is unrecognizable to present me.

I also have suspicions that a past life journaling semi-publicly might somewhat compromise the efficacy of the type of private journaling this therapist was advocating for. I’m not sure when the psychologist said “journal about your anxiety” he meant “tell the world about your ICD-10 Diagnoses in your next Substack newsletter.”

Now that my comprehensive exams are over, I’m beginning to plan out my dissertation proposal/prospectus, which I will need to defend this fall. The approval of this document is what would result in me being “ABD” (All-But-Dissertation), which finally moves me on to the last phase of my PhD program: the dissertation itself. Which, if you’re new here, will come in the form of a creative writing project (a novel). For our purposes, I will just refer to this manuscript by a code name: Project Fire.

This proposal document is not just about outlining the novel I want to write; it’s also about trying to situate it in literary theory and history. I don’t mind the process. In my college years, before I ever started to take creative writing seriously, I was a fine arts major, so the process of stepping outside of yourself to inspect your body of work as a quasi-critic isn’t foreign to me. What I do find strange is just how many artist statements I had to write when I was a visual arts student compared to how few I’ve had to write in creative writing classes. Maybe as an introduction to a final portfolio. One or two statements of poetics1 in graduate school. But these all tended to be about poetry—not fiction. I wonder if this is because moving from visual media to text can present some sort of intuitive alchemy in a way that moving from text to text (especially prose to prose) does not? In any case, I don't feel like creative writers have the opportunity to speak critically about their own work often enough.

Maybe because I’ve done this all before, I feel rather calm about trying to intellectually define and situate a book that does not exist, despite how objectively crazy that all sounds. It’s like being asked to measure a ghost for a tuxedo. I mean, I do have around 20,000 words at this point in Project Fire—and a few different outlines and syuzhets. What’s been helpful for me, when conceiving of this prospectus, is beginning by thinking of genres and types my novel might feel connected to. Without saying too much more about the exact plot of my novel-in-progress, these are some of the lineages or groupings I find it will be in conversation with:

Literary lineages or types Project Fire is in conversation with

The Millennial novel2

E.g.: generation gaps between Millennials and Gen X/Boomers

Midlife (or quarter-life) crisis narrative

Metafictional narrative

Mystery novel

Investigative/detective narrative elements

The New York novel

Florida literature/regionalist writing

The contemporary Gothic novel

Particularly the Southern Gothic

The Künstlerroman, i.e., the artist’s novel

The road trip novel

The queer novel

E.g.: imagining and speaking to a queer audience; not going out of the way to teach the heterosexual/cisgender reader one’s own cultural reference points

Novels of sexual identity and religious conflict, i.e., the “queer trauma narrative”

Surviving conversion therapy and schools where abuse took place

While I would like to get started on my proposal sooner than later, I do often find the most pleasure in the discovery phase of writing. This is when I am just researching, thinking, outlining, clustering, and brainstorming. I often compare it to putting your fingers on the planchette of a Ouija board and feeling for a spectral voice. Part of this process involves leaning into the unknown—or trusting that your gut instincts will lead you closer to knowledge. For the past couple of days, I’ve been ruminating on this idea of what makes a Millennial novel a Millennial novel, and why am I personally attracted to that affinity category for this project.

The immediate self-indulgent answer to my interest in this category is that I am a Millennial, and I do not feel that I’ve poured some of my own generational experiences into any of my writing quite to the degree in which I believe I will do in this unwritten manuscript. Secondly, one of my two main characters, who I will just call “U,” is very much focused on his position in the world as a Millennial: he has a resentment toward older generations that he believes “got theirs”; he feels that the harder he works, the more he fails; he has extreme economic anxieties that result from entering a failing workforce during the Great Recession. When I was thinking about “U,” I had wondered just how much scholarship is out there on “Millennial fiction” at this point—and what would be the unifying factors for such a grouping.

If we use the Pew Foundation’s definition of “Millennial”3 (born between 1981–1996), our oldest writers are currently 44 as of this newsletter. For those who have been publishing since their twenties, there are certain writers who have had over two decades now to develop a repertoire. I do want to clarify, before going any further, that I have a healthy distrust of these generational groupings. Their attempts to group have a tendency to erase the experiences of “outliers.” It can be easy to, for example, group a bunch of different people together by birth year without considering nationality, immigrant status, class, race, sexuality, metropolitan versus provincial status, access/exposure to technology and pop culture, etc. So, with the implicit understanding that there will probably be some ethnocentricity around Western/US culture and other dominant cultural markers, I’d like to point out a few items that the Pew Foundation mentions when trying to tie together Millennials (filtered through my own editorialization):

Shared Identity Markers between Millennials

Memories of 9/11 and the War on Terror beginning in youth/adolescence

I would add that these historical experiences are filtered through:

a sense of government dishonesty (lies about Weapons of Mass Destruction)

governmental clandestineness (the war was not broadcast in the same way that the Silent Generation and Boomers watched the Vietnam War live on television; nor was this after everything could be instantly filmed on smartphones and uploaded to become viral social media posts like Gen Z is used to)

domestic surveillance (i.e.: NSA spying on US citizens, Patriot Act).

Sense of politics heavily influenced by the administrations of George W. Bush and Obama (for those in the U.S.)

Entering the workforce during the height of an economic recession; feeling like their adulthood was “delayed” or received a “slow start” because of occupational or economic insecurity

Tensions about “just missing out” on what Gen X got or “never getting” what Boomers had access to

I’d add the psychological effects of simultaneously inheriting a financially ruined world and unstable economy that Boomers and the Silent Generation were responsible for destroying—and then being criticized/victim-blamed for financial habits and lifestyle choices (from the very people who were at fault) despite limited opportunities to build wealth

Early adopters to the gig economy and the technology connected to it (e.g.: Uber, TaskRabbit, Etsy…)

Having a strong binary sense of before/after with technology (the “before” being a childhood more connected to analog media or a sense of “without,” i.e.: being “logged off” as this very deliberate state that is different from feeling “always connected” to the internet)

Life before/after having a computer [connected to the internet]

Life before/after social media

Life before/after texting became standardized on phones (i.e.: the sense that you could be reached atf all times)

Life before/after smartphones (i.e.: having a camera and internet access with you always)

Experiencing technology with an emphasis on writing/reading text and producing long-form media (as opposed to apps that encourage/promote images, video, and short-form content)

E.g.: Blogger/Blogspot/LiveJournal/Xanga/Tumblr

E.g.: internet forums

The “before” (analog childhood) creating a connection or nostalgia for analog tech/physical media

Having an adolesence that felt connected to rapidly growing technology, particularly with the internet; almost a spiritual connection to one’s own puberty matching the internet’s own “puberty”

E.g.: starting out with no internet, moving to slow dial-up internet, ending up with high-speed cable internet

E.g.: starting out with no cellphone, moving to “dumbphones,” ending up with smartphones

E.g.: starting out with paper maps, moving on to printing out MapQuest directions, ending up with hyper-accurate GPS built into their phones with map apps

Experiencing growing/changing technology with optimism, hope, or the genuine excitement of early adoption (before billionaire domination/anti-competition and enshittification)

Experiencing media at “appointed times” rather than unlimited, on-demand access

E.g.: TV shows aired at certain days and times and were not accessed on-demand whenever you wanted

Everything I’ve outlined above are sweeping generational gestures though (and no doubt filtered through my own experiences/biases)—and more about Millennials as human beings rather than an artistic class. The question is: are there similarities, aesthetics, themes, or shared choices that occur when Millennials sit down to write fiction—particularly the novel?

An article published on Book Riot from 2023 titled “What is the Millennial Genre?” argues that “The concerns of millennial novels are more fractured, most likely because of the dissolution of the monoculture and the growing diversity of published authors that allows us to read widely about many different people.” Inevitably, when it becomes time to invoke names, Sally Rooney is the first to be summoned. Born in 1991 (currently 34), Rooney published her first novel, Conversations with Friends, in 2017 (when she was 26). As of 2024, she’s published four novels. Book Riot says this of Rooney’s prose: “The focus of her novels turns inward to allow her characters to explore the oppressive anxieties of living in a world where it feels like everything is stacked against you.”

It seems one aspect of Rooney’s writing that feels distinctly “Millennial” is inheriting a failing world and the anxiety of feeling like you cannot succeed in it. Others note how Rooney’s minimalist prose and emotionally hyper-detailed focus echo the digital-age self-scrutiny of text messages, DMs, and online confessionals. While I’d sign on to this idea of hypertextual fluidity with different digital modalities to be connected to Millennial writing, I’m wary of associating Rooney’s minimalism with a distinctive Millennial aesthetic rather than a personal stylistic choice (signed, a maximalist).

I’d also wager it would be reckless to inherently associate Millennial writing with left-of-center politics, but something about Rooney’s writing that does feel distinctly Millennial to me is that our politics often have to be filtered through a distrust of power, economic burnout, malaise, a sense of being psychically paralyzed, and ambivalence (more on literary ambivalence in a moment).

The Book Riot article calls back to an earlier Guardian article from 2019 (“Darkly funny, desperate and full of rage: what makes a millennial novel?”) which highlights Rooney beside eight other Millennial authors. It offers this as an element of Millennial fiction:

In contrast to the ways they are marketed and their media reception, millennial novels, if they have a common aim, push against labels, pedestals and the uncritical lauding of spokespeople. They care more about being relatable to a specific audience than a universal one. This resistance, bordering on impostor syndrome, is part of what makes them feel true to the millennials who read them. The protagonists of these novels eyeroll at marketing taglines, tired hierarchies, male canons and influencers. Self-definition is a millennial forte, but its novelists seem dubious of anything so earnest as defining a literary epoch. Their fictional worlds lambast our need for external validation and commodified selfhood of the kind that feeds late capitalism, even as they acknowledge their complicity and the impossibility of extrication.

What Sudjic is arguing here is that Millennial novelists inherently resist the very thesis I’m sitting down to address—i.e., ‘what is Millennial fiction?’ What is being argued is that Millennials are skeptical of trying to declare an affinity that would place a crown on one’s own head as the voice of their generation (although I’m sure we could all think of some outliers). In general, though, I do think it’s fair to say that individual Millennial writers eschew being seen as ‘the voice of their generation.’ I.e.: authors try to resist being labeled or being turned into generational figureheads. And it is this very refusal to claim authority that feels authentic to Millennial readers—which in a way are the primary audience of Millennial writers. Considering the world that Millennials have inherited, it would make sense that uncertainly-as-affect might transcend toward humility. It’s also possible, as one of the first generations who had to grow alongside their “second selves,”4 Millennials grew with a hyper-awareness toward carefully curating their identities, as they often had to meticulously maintain one on social media.

Beyond Sally Rooney, Rittenberg and Sudjic name-drop a few writers/novels that often get repeated when the topic of Millennial fiction arises: My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh (b.1981), Severance by Ling Ma (b. 1983), and Luster by Raven Leliani (b.1990)—to name a few. As novelists tend to get top billing, it made me also wonder about short fiction. After all, some of the most viral short stories from the past decade—particularly the ones with a literary affect—have been penned by Millennials: “Cat Person” by Kristen Roupenian (b.1982) and “The Feminist” by Tony Tulathimutte (b.1983). Isabel Fall, a pen name for a writer who wrote the speculative “I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter,” was chased off the internet for naming her story after a trans-antagonistic copypasta5. Fall (b. 1988), arguably embodies some aesthetic of Millennial ambivalence by ‘not making her positionality clear,’ as MFA students love to say in creative writing workshops. Fall, a trans woman who was repurposing a transphobic meme in her art-making, was assumed to be a bad actor and a troll for this title—despite doing something genuinely intertextual and transformative.

Roupenian and Tulathimutte may share some of that literary ambivalence too when it comes to identity and narrative. “Cat Person” deals with dating in the app era, filtering attraction through curiosity, flirtation, repulsion, and anti-catharsis. “The Feminist” features a male self-identified feminist who is self-deluded, desperate for moral approval, hypocritical in his sexual and social behavior—all while asking for some sympathy (or at least pity) because he’s simultaneously genuinely lonely, realistically insecure, and famished for acceptance. Both writers gesture toward cultural and political movements that developed on the internet (i.e.: #MeToo, redpill/manosphere/MRA).

In terms of defining the great Millennial aesthetic/voice/theme, Tulathimutte was quoted in a Guardian interview saying, “If I had to name a contender for the great millennial theme it would be resentment.”

Although, I wonder if one should be more careful about associating Millennial literary aesthetics solely with ambivalence or even negative affects. On the opposite end of aesthetic, there is undoubtedly Millennial certainty and righteousness, especially when it comes to political determinations. When held up against common generational associations with Gen X (slackerdom, cynicism, cool detachment) or Gen Z (nihilistic, skeptical of ‘toxic positivity’), I’d wager Millennials are more commonly associated with emotional authenticity, candid vulnerability, and sincerity (even if it is self-reflexive and filtered through residual irony).

As far as some of my cursory research went, I also wondered if there was some deeper scholarship beyond just literary websites and newspaper articles. To my surprise, I ended up finding out that The Edinburgh Companion to the Millennial Novel is being published at the end of next month (August 2025). The PDF version of the ebook is apparently already out (and on JSTOR), but unfortunately I don’t have the proper institutional access, so for now I’ll have to put a pin in what may be the next monumental text in helping me think through this question of the “Millennial novel.”

The Companion promises to “offer a global framework for thinking about the dominant forms and preoccupations of writing by millennial authors; bring together emerging and established scholars from literary and cultural studies; engage with major theoretical developments—in queer studies, post-colonial studies, affect studies, narratology, race studies, etc.—to better understand the genre and millennial sociality.”

While I can’t say much about its contents, it did make me wonder if literary criticism is reaching a turning point toward asking some deeper questions about writing from Millennials. It also made me wonder if some of the reason it’s taken so long to get here is connected to the same generational ‘delayed adulthood’ that has perhaps made publishing a longer journey for people around my age.

The last academic nugget I’ll offer up is from The Encyclopedia of Contemporary American Fiction 1980–2020, which came out in 2022. There is a chapter on “Millennial Fiction” by Scott McClintock. McClintock uses the term “Millennial” more fluidly, having it stand in not only for the generation, but “Y2K fiction” as well that emerged around the year 2000 (for the latter, this includes authors of all generations). What I find fascinating about this flattening of “Millennial” is how it becomes a cipher for all the anxieties that a new millennium would bring.

For those of us old enough to remember the turn of the century, once upon a time there was this theory that a computer glitch would occur when December 31, 1999 transitioned into January 1, 2000. The story went: entire ecosystems of technology would crash worldwide! Planes would fall out of skies! The stock market would crash! There were people who even thought this rumored glitch would lead to a complete apocalypse. Some people even created underground bunkers, filling them with canned food, guns, generators… As someone who personally also read some of the Left Behind novels (Christian eschatological fiction based on the Book of Revelation) in the years leading up to the millennium, there seemed to be some zeitgeist between media, secular and religious apocalyptic thinking, and the dawn of the 21st century.

Something McClintock also calls attention to is the rise of young adult fiction as it intersects with apocalyptic (and post-apocalyptic) fiction. Regarding the former, it makes me wonder if the rise of YA fiction in the 21st century into its own unique market with its own identifiable tropes might in some way share a connection to Millennials (both as readers and writers) and their relationship to a delayed adulthood. Although Suzanne Collins is certainly not a Millennial, she did open a space for this discussion about the failures of nation-states and what apocalyptic events occur in the aftermath of failure—conversations that were picked up by Millennials such as Veronica Roth, the author of the Divergent series. McClintock writes:

If the nation is seen to be a broken community, both of these novel cycles portray communities of solidarity (what Thomas Beebe refers to as “apocalyptic communities”) that resist totalitarian control in a postapocalyptic setting. As in much postapocalyptic fiction, nation-states are survived by city-states, and the postapocalyptic landscape is also a postnational one. Other Millennial fiction in the generational sense focusing on postapocalyptic plots set in cities and representative of the increasing ethnic diversity of this genre includes Susan Ee’s Angelfall (2012), Julie Kagawa’s The Immortal Rules (2013), Tochi Onyebuchi’s War Girls (2019), Victoria Lee’s The Fever King (2019), N.K. Jemisin’s The City We Became (2020), and Lilliam Rivera’s Dealing in Dreams (2020).

Although much of the public imagination of “Millennial fiction” has been taken up by authors of literary fiction, McClintock’s definition makes space for speculative writers that I hadn’t seen as openly discussed in other articles. Apocalyptic strain, global anxieties (climate crisis, pandemics, technological collapse…), late-capitalist economies (“fast capitalism”), the “new work order” under capitalism all contribute to Millennial speculative aesthetics. As McClintock notes, Ling Ma’s Severance exemplifies this because A) a pandemic reduces people to zombie-like routines, B) the narrator’s corporate job, producing specialty Bibles in a globalized system, epitomizes how identity dissolves into repetitive labor, and C), the novel doubles as an apocalyptic survival story and a workplace satire.

McClintock also notes that many Millennial novels are defined by ethnic and cultural diversity that increasingly draws from transnational experiences (e.g.: Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous) and a post-ethnic and post-generational sensibility that resists unifying labels (which goes back to Sudjic’s argument that Millennial writers resist encapsulating themselves as the voice of their generations).

I don’t know if all these claims about Millennial fiction bring us closer to a simpler, easily-agreed-upon definition, but they do introduce some patterns that various thinkers might be in agreeance on. In any case, it’s given me more to consider about what it would mean to write my own “Millennial novel” and where it could possibly fit in among my peers.

When being tasked with journaling for mental health reasons brought me back to my teens and twenties, I decided I might as well be fully self-indulgent and pull out some of my old journals from around 2006-2008 (my college years). This wasn’t just purely for navel-gazing purposes. Often doctors will ask me when I first started to feel anxious or depressed (“always”), and I’ve never really gone back and analyzed past versions of myself with the only remaining documents I have. So, I thought—why not. I could almost pretend to be a therapist, inspect a textual past version of me as if they were a stranger. It’s odd to be doing this on the same day I’m deeply meditating on Millennials as a literary class. That thought has bled into everything. In some ways, that version of me twenty years in the past feels more like a Millennial than I do in my present. I want to tell you why, but I think I already have.

I dived in to these old journals, reading words of a past version of me who is more mysterious than I could have ever guessed. I was anxious in my journal entries, especially the ones right before I graduated college. I don't think I had heard that the Recession was coming at this time, or at least I wouldn't know it was here until it was too late. I was so stressed about this post-college job world that seemed so unfathomable, impossible. My parents knew nothing of college, only that it was something I was supposed to do. They had no practical advice for me, especially regarding what happens after those four years. My father—a white man, a Baby Boomer—belonged to the era of printing out your résumé, going into a place of business, asking to see someone in person, and giving them a firm handshake. In Boomer logic, perhaps I was supposed to just magically get a job after graduation. It would happen because it was supposed to happen. Instead, I entered the workforce at the daybreak of an economic recession when job applications meant you sent hundreds of emails into a void, never to be answered again. I journaled about having an existential dread that my youth was slipping away, and it’s no wonder why.

Not all past versions of me I admire—or even think of with any fondness at all. There were a lot of past selves who were assholes. But something I was surprised—or maybe something I had forgotten—was how incredibly sensitive I was during that time window, away at college—away from Florida—for the first time. I was hurt. I was lonely. I was immature, sheltered, homesick, socially anxious, afraid to leave the house, suffocated by falling in love with the wrong people who could not—would not—love me back, obsessed over this thought that I would become a failure in the future.

That person in the past was a wounded bird, and I didn’t realize how much I would long to protect them from harm in this present. It's hard to want to save someone who you can't save. It's harder when they exist at a different place and time. It's hardest when that person is you.

I wish I could go back—through the time and space—to hold them. I would tell them that soon you will grow up, and you will grow up fast. You will have your experiences. You will fail—but you will not become a failure. You will survive more than you can ever know. You will become tough as nails. You’ll still be sensitive, though. The anxiety will change—get worse, even—but that’s okay. The depression, it will change, but it, too, will stay. They’ll become part of you, like many things will, whether you like it or not. Few things are temporary. They become part of a life’s work. And you will write about all of these things one day. Because you are a Millennial after all: dry and ironic, effusive at times, emotionally authentic, candid and vulnerable—and above all else—disgustingly sincere.

Until next time,

J

A statement of poetics is essentially a poet’s artistic credo. It’s typically a prose document in which the poet explains their approach to poetry; clarifies their artistic aims and motivations; discusses influences, aesthetics, and principles; and articulates their methodology.

Spoilers: this is what this entire newsletter is ultimately about, and if you do not like my choice to capitalize “Millennial,” then you can go suck on a lemon.

"The term Second Self is a way of describing one's online or external identity. In the case of the web, one's online identity evolves in tandem with offline self. This self, instead of simply a secondary self, is becoming an extension of the self. In the same way that the primary, offline self needs to shower, dress, and maintain the self, so does the online self.”

A block of text copied and pasted to the Internet and social media. Often this is for meme purposes, trolling efforts, or to make those ‘in the know’ laugh. It also serves as an insider/outsider litmus test between those who know it’s a copypasta and those who think it’s original, genuine text.